September 6, 2023 • 9:00 am ET

Sleight of hand: How China weaponizes software vulnerabilities

Table of contents

Executive summary

The Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), the Ministry of Public Security (MPS), and the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) published the “Regulations on the Management of Network Product Security Vulnerabilities” (RSMV) in July 2021. Even before the regulations were implemented in September 2021, analysts had issued warnings about the new regulation’s potential impact. At issue is the regulations’ requirement that software vulnerabilities—flaws in code that attackers can exploit—be reported to the MIIT within forty-eight hours of their discover by industry (Article 7 Section 2). The rules prohibit researchers from: publishing information about vulnerabilities before a patch is available, unless they coordinate with the product owner and the MIIT; publishing proof-of-concept code used to show how to exploit a vulnerability; and exaggerating the severity of a vulnerability. In effect, the regulations push all software-vulnerability reports to the MIIT before a patch is available. Conversely, the US system relies on voluntary reporting to companies, with vulnerabilities sourced from researchers chasing money and prestige, or from cybersecurity companies that observe exploitation in the wild.

Software vulnerabilities are not some mundane part of the tech ecosystem. Hackers often rely on these flaws to compromise their targets. For an organization tasked with offensive operations, such as a military or intelligence service, it is better to have more vulnerabilities. Critics consider this akin to stockpiling an arsenal. When an attacker identifies a target, they can consult a repository of vulnerabilities that enable their operation. Collecting more vulnerabilities can increase operational tempo, success, and scope. Operators with a deep bench of tools work more efficiently, but companies patch and update their software regularly, causing old vulnerabilities to expire. In a changing operational environment, a pipeline of fresh vulnerabilities is particularly valuable.

This report details the structure of the MIIT’s new vulnerability databases, how the new databases interact with older ones, and the membership lists of companies participating in these systems. The report produces four key findings.

- The RMSV (Article 7, Section 3) requires the MIIT’s new database to share vulnerability and threat data with the National Computer Network Emergency Response Technical Team/Coordination Center of China (CNCERT/CC) and Ministry of Public Security (MPS). Sharing these data with CNCERT/CC allows them to reach organizations with offensive missions. CNCERT/CC’s partners can access vulnerability reports through its own China National Vulnerability Database (CNVD). The CNVD’s Technology Collaboration Organizations with access to reports submitted to MIIT include: the Beijing office of the Ministry of State Security’s (MSS) 13th Bureau (Beijing ITSEC, 北京信息安全测评中心), Beijing Topsec—a known People’s Liberation Army (PLA)-contractor connected to the hack of Anthem Insurance, and a research center responsible for “APT [advanced persistent threat] attack and defense” at Shanghai Jiao Tong University, which houses a cybersecurity school tied to PLA hacking campaigns. The vulnerability sharing with the MSS 13th Bureau’s Beijing office is particularly concerning. Experts note that the bureau spent the last twenty years getting early access to software vulnerabilities.

- There are likely bureaucratic issues involved in implementing the RMSV among relevant entities. Mandatory disclosure of vulnerabilities to MIIT undercuts other, government-run, voluntary databases in China. CNVD disclosed fewer vulnerabilities after the regulation went into effect, and its publication of vulnerabilities for industrial control systems ground to a halt in 2022. This decline is likely the result of CNVD waiting for a patch before publishing. With no reporting requirement, and the inability to publish without a patch, the value of the voluntary database is unclear. One benefit may be collection. CNCERT/CC has incident-response contracts with thirty-one countries. It is unclear if these contracts allow CNCERT/CC to collect vulnerability information.

- Besides just collecting software vulnerabilities, the MIIT is funding their discovery through research grants to improve product security standards.

- An MSS vulnerability database requires its private-sector partners to produce software vulnerabilities. These 151 cybersecurity companies provide software vulnerabilities to the MSS 13th Bureau. This report finds that these companies employ at least 1,190 software vulnerability researchers. Each year the researchers provide at least 1,955 software vulnerabilities to the MSS, at least 141 of which are “critical” severity. Once received by the MSS, they are almost certainly evaluated for offensive use.

The mandates to disclose vulnerabilities to the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, not to publish vulnerability information without also simultaneously releasing a patch, not to release proof-of-concept code, and not to hype up the severity of a vulnerability, among other things, stands in stark contrast to the United States’ decentralized, voluntary reporting system.

Introduction

Software vulnerabilities are like raspberries—they go bad fast. For intelligence services and militaries that seek to hack an adversary’s systems, having vulnerabilities on hand is key. Software vulnerabilities are flaws that allow an attacker to exploit the software and achieve a desired effect. Knowing which software vulnerabilities operators will need in advance is challenging, so having many on hand is incredibly useful to support operational tempo. But because companies are usually quick to patch their products, a trove of software vulnerabilities, however well-stocked, is quickly rendered useless if not replenished regularly.

Over the last six years, China has taken significant steps to collect more vulnerabilities. China’s Ministry of Public Security prohibited cybersecurity experts from traveling to foreign software security competitions in 2017, where they would burn vulnerabilities in commonly used tech for hundreds of thousands of dollars. Preventing researchers from attending international competitions that made everyday products more secure was not only a loss for defenders; China explicitly gained more vulnerabilities for offensive use. One company, Beijing Chaitin, told a media outlet that it would prioritize submitting vulnerabilities to the MSS-run CNNVD database instead of participating in foreign competitions. China’s top cybersecurity policymakers and corporate executives share the “collect them all” attitude. The chief executive officer (CEO) of Qihoo360 remarked in the same year that software vulnerabilities are “important strategic resources” that “should stay in China.” Also in 2017, China launched a series of competitions to promote the development of technology that could automate the discovery, exploitation, and patching of software vulnerabilities. The same Qihoo360 CEO called the technology an “assassin’s mace”—or in Department of Defense (DOD) jargon, a strategic offset. Together, the policies prevented China’s strategic resource from being leaked overseas and invested money in technology to make finding vulnerabilities more efficient. Still, the government could only ever receive vulnerabilities that were voluntarily provided to it.

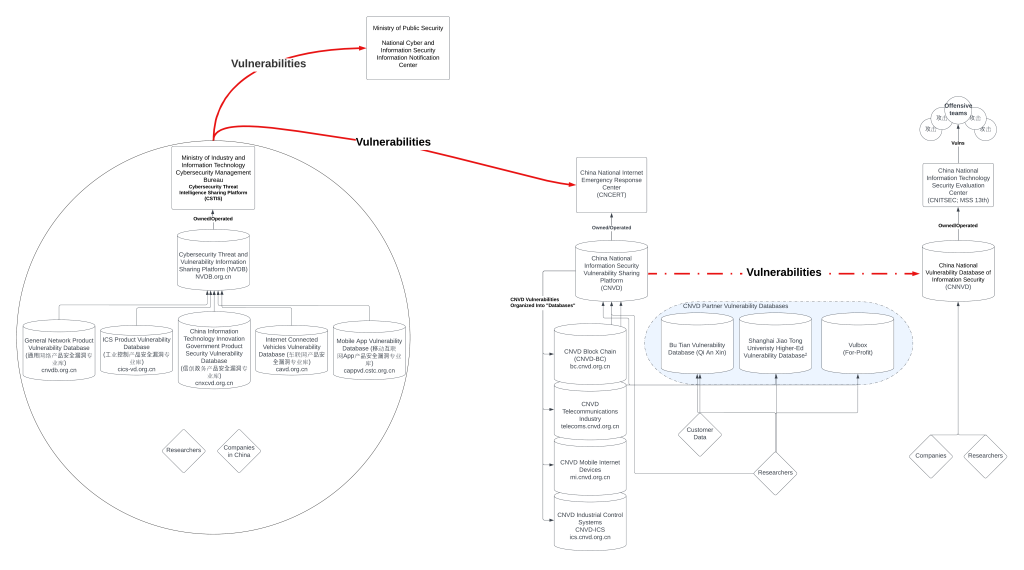

China developed a system to collect software vulnerabilities that previously escaped its reach. Under the old system, the government did not collect vulnerabilities found by, or reported to, companies. Companies often find vulnerabilities in their own products. Many firms also receive external reports from researchers, sometimes in exchange for money. The 2021 RMSV—written by the CAC, the MPS, and the MIIT—expanded the government’s collection to include these sources. The new rules require companies doing business in China to report software vulnerabilities in their products or products they use to the MIIT within forty-eight hours of discovery. The regulations stop independent researchers from publishing information about vulnerabilities without coordinating a patch with the company, releasing proof-of-concept code that shows how to exploit a vulnerability, and hyping up the severity of a vulnerability. The requirement to coordinate the vulnerability disclosure with the business pushes the vulnerability into the MIIT’s new system, because the company must report it within two days. At some point after the Cybersecurity Threat and Vulnerability Information Sharing Platform receives the vulnerability, MIIT shares it with the MPS and CNCERT/CC. The 2021 regulations are aligned with People’s Republic of China (PRC) policymakers’ attitudes toward software vulnerabilities, which began coalescing in 2017.

Three earlier reports contour China’s software vulnerability ecosystem. Combined, they demonstrate a decrease in software vulnerabilities being reported to foreign firms and the potential for these vulnerabilities to feed into offensive operations.

First, the Atlantic Council’s Dragon Tails report demonstrates that China’s software vulnerability research industry is a significant source of global vulnerability disclosures, and that US legislation prior to China’s disclosure requirements significantly decreased the reporting of vulnerabilities from specific foreign firms added to the US entities list, removing an important source of security research from the ecosystem.

Second, Microsoft’s “Digital Defense Report 2022” showed a corresponding uptick in the number of zero-days deployed by PRC-based hacking groups. Microsoft explicitly attributes the increase as a “likely” result of the RMSV. Although less than a year’s worth of data do not make a trend, both reports gesture at the impact of the regulation in expected ways, based on China’s past behavior of weaponizing the software vulnerability disclosure pipeline.

Third, Recorded Future published a series reports in 2017 with evidence indicating that critical vulnerabilities reported to China’s National Information Security Vulnerability Database (CNNVD, run by the MSS) were being withheld from publication for use in offensive operations.

This report adds to these findings. Specifically, we find that the 2021 RMSV allows the PRC government, and subsequently the Ministry of State Security, to access vulnerabilities previously uncaptured by past regulatory regimes and policies. In some cases, the regulations also facilitate access to some companies’ internal code repositories.

China’s software vulnerability disclosure ecosystem

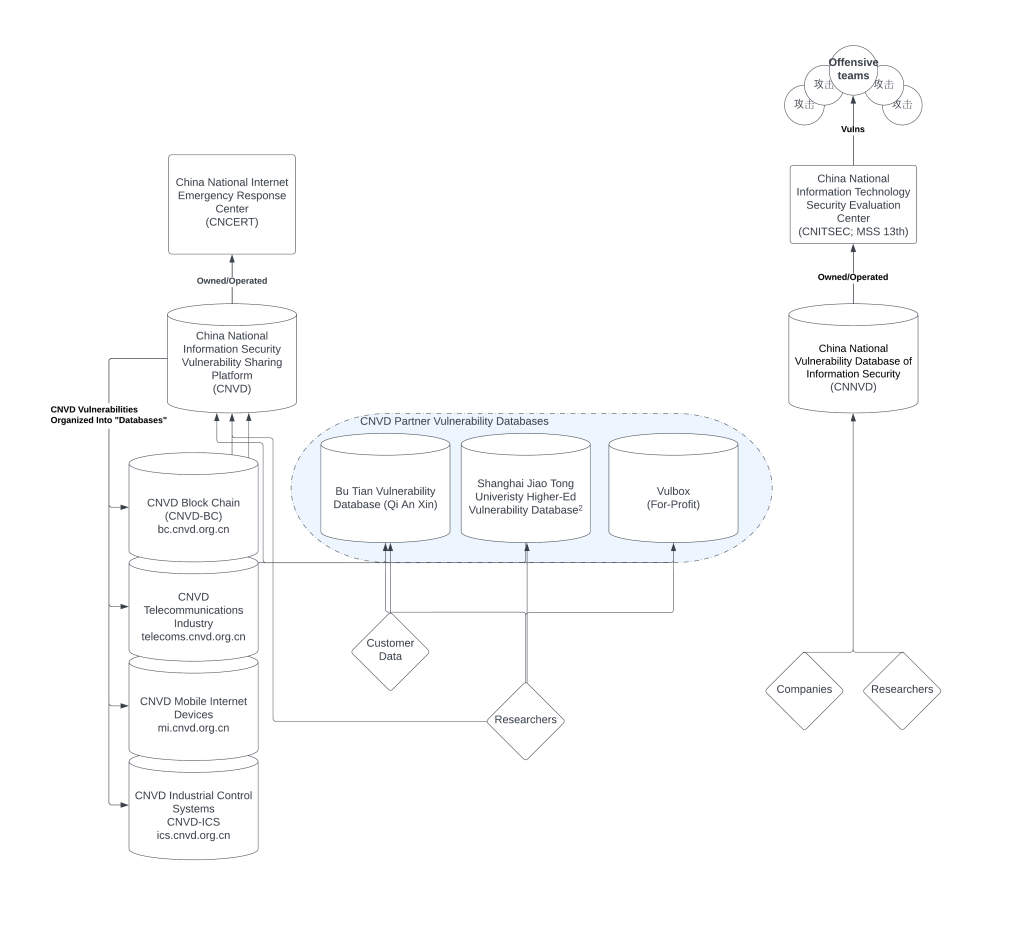

The following graphic illustrates the relationships within China’s government-run software vulnerability ecosystem. This report does not cover actors on the black market or their impact on this system.

Before the RMSV

China National Vulnerability Database

The CNVD, run by CNCERT/CC, is meant to help defend computer networks in China and other nations, like the US National Vulnerability Database (NVD). CNCERT/CC maintains joint incident-response contracts with at least thirty-one other national community emergency-response teams (CERTs), though which countries participate is unknown. CNVD users receive advanced warning of software vulnerabilities from the database. These vulnerabilities are collected from voluntary reporting by individuals or companies, or from a partnering vulnerability database.

The CNVD collects some of its data from three CNVD partner vulnerability databases, each with its own list of contributors: the Higher-Ed Vulnerability Database, Vulbox, and the Bu Tian Vulnerability Database.

Shanghai Jiao Tong University operates the Higher-Ed Vulnerability Database. The database collects vulnerability reports on products used by institutions under the Ministry of Education. Researchers, professors, and students voluntarily submit vulnerabilities. The products have a variety of national origins and are not just education-related software. The university organization operating the vulnerability database also teaches defense-industry and government employees “secrets theft and anti-secrets theft” skills on another platform. SJTU has supported PLA hacking campaigns and is home to a center that conducts research on “APT attack and defense.”

The other two databases feeding the CNVD rely on the private sector. Vulbox is a for-profit vulnerability disclosure marketplace. Like similar companies in the United States, it connects white-hat hackers to companies looking to secure their products. Companies pay researchers who find vulnerabilities and submit them through the platform. Vulbox shares these vulnerabilities, paid for by corporate incentive, with CNVD. Qi An Xin, a premier cybersecurity firm, maintains the other database. The Bu Tian Vulnerability Database is a forum for white-hat hackers to discuss software vulnerabilities. Users can share vulnerability reports, help other users recover from attacks, and join an annual competition. Both databases draw on unique sources of vulnerabilities: Vulbox from software security researchers cashing in on their work; Bu Tian from researchers discussing new findings, recovering from incidents, or discovering new vulnerabilities at the annual Bu Tian Cup software competition.

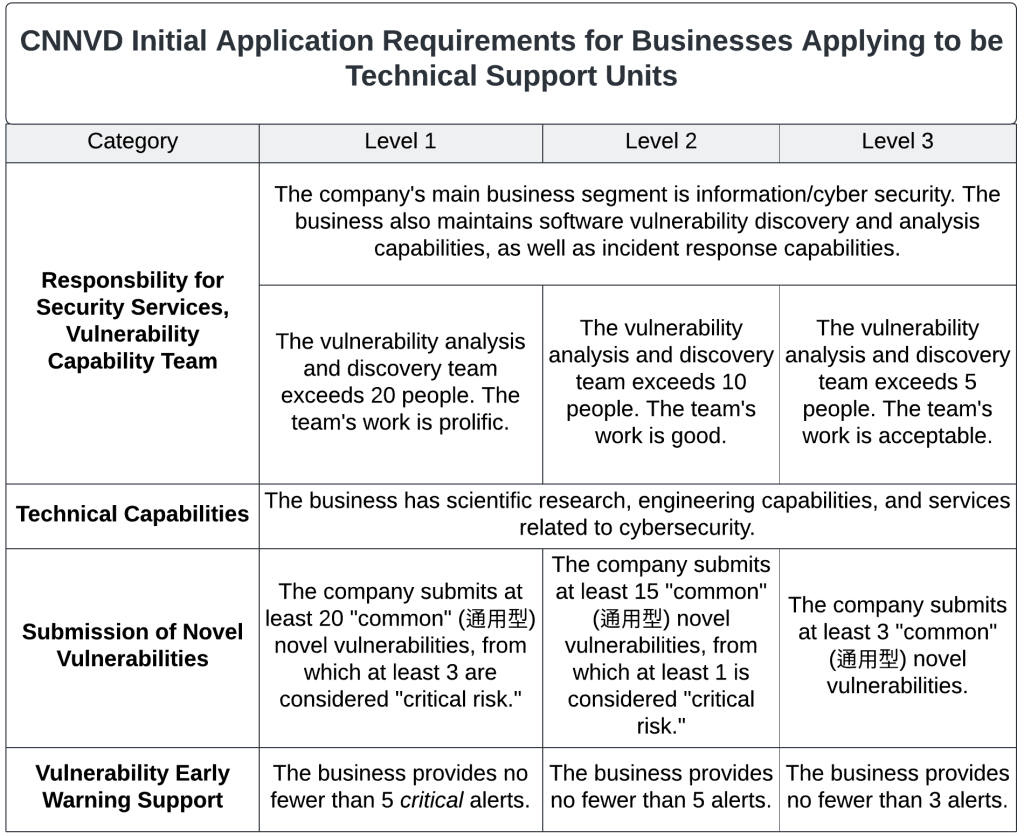

The CNVD also receives voluntary vulnerability reporting from researchers and cybersecurity companies. Under the 2021 regulations, these companies must also report the vulnerabilities to the MIIT’s new database (see discussion below). CNCERT’s 2020 annual report graded the capabilities of its technical supporting organizations, ranking their capabilities to collect, analyze, and discovery software vulnerabilities. The criteria to produce the evaluation and rankings are not in the report, but they can be found online. This report reproduces that table below and flags (with an asterisk) seventeen of the twenty-six companies that also support the MSS-run CNNVD with an asterisk. Under the RMSV, CNVD now receives software vulnerabilities from the MIIT’s new database.

Source: CNCERT/CC 2020 Annual Report

CNVD distributes vulnerability data to its technology collaboration organizations. These organizations are meant to integrate the data into cybersecurity services they provide to customers. Some organizations and companies may use this vulnerability distribution to support offensive operations. These organizations include the Beijing regional office of the MSS 13th Bureau (北京信息安全测评中心), a known PLA contractor tied to the hack of Anthem Insurance called Beijing TopSec, and other prominent government-servicing cybersecurity firms such as Qi An Xin, which runs its own Cybersecurity Military-Civil Fusion Innovation Center (网络空间安全军民融合创新中心). Even the Shanghai Jiao Tong University Center (上海交通大学网络信息中心) responsible for “advanced persistent threat attack and defense” research makes this list of integrators.

Separately, another group of thirty-eight CNVD user-support organizations help defenders integrate vulnerability data into their network defenses. The role of international partners in vulnerability sharing, collection, use, and defense is unclear. A list of CNCERT/CC’s international partners is not available, nor are the contracts that underpin their relationship. CNCERT/CC responded to a request for comment by pointing to the organization’s press-release website.

CNVD also maintains four databases for software vulnerabilities, but these appear to be maintained as a single database, do not require separate accounts to access, and are subdomains of the CNVD website. This structure merely sorts the CNVD system, rather than distributing vulnerabilities into unique repositories.

Data from one of these four databases—the industrial control systems (ICS) vulnerability database—make clear how significantly the RMSV decreased public vulnerability disclosure. While a few hundred vulnerabilities were disclosed by the ICS database each year from 2018 to 2020, 2022 saw just ten vulnerabilities published in this system. In the same year, the US Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) recorded 113 exploited ICS vulnerabilities.

The near total drop-off in publicly reported ICS vulnerabilities was accompanied by a significant decrease in the total vulnerabilities disclosed by CNVD.

The data suggest there is a significant gap between actual and disclosed ICS vulnerabilities. If researchers find a number of ICS vulnerabilities similar to the number before the regulations, and they report them to the new MIIT database for ICS vulnerabilities, then the vulnerabilities would still show up in CNVD data, albeit with a delay. Although the MIIT database does not publish vulnerabilities publicly, the 2021 regulations require the MIIT to pass them along to the CNVD. If the MIIT had reported the vulnerabilities to the vendors, then CNVD would have published the vulnerability data when the company released the corresponding patch—but the data do not show this. Instead, the data suggest that companies, at least ICS companies, are not receiving vulnerability reports from the MIIT.

China National Vulnerability Database of Information Security

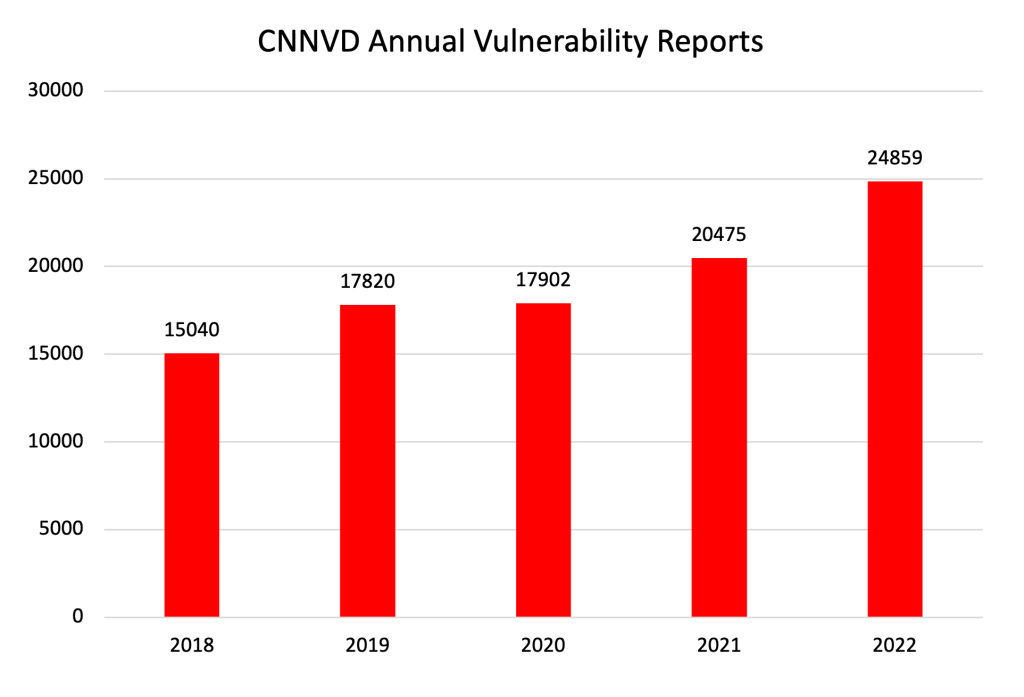

China has, in the past, weaponized software vulnerabilities provided to its CNNVD, which is run by the MSS. Statistical analysis by Recorded Future in 2017 demonstrated that the intelligence service likely passed high-criticality vulnerabilities to its hacking teams and delayed their public disclosure. After its operations were burned when another entity publicly disclosed the vulnerability, the MSS would disclose them as well and move on. The reports by Recorded Future made clear the operational value the CNNVD offered to China’s offensive hacking teams.

Unlike the CNVD, the number of CNNVD published vulnerabilities continues to trend upward. This is not because of the goodwill of the MSS. Each vulnerability reported by CNNVD can be tied to other public data, like a GitHub repository or a company’s website, meaning the database is not offering new information. In effect, CNNVD data just reflect what is publicly observable. In a humorous twist, monthly reports from the CNNVD used to compile the chart below stop in November 2017, the same month Recorded Future researchers published their report. After being caught, the MSS wiped its website of historical data and started fresh.

Based on the requirements for firms supporting the MSS-run CNNVD, the exploitation of vulnerabilities provided to the database seems to continue today. This assessment is unsurprising, given the MSS 13th Bureau oversight of the database. The clarity of the requirements for members to produce vulnerabilities that can be used in hacking campaigns is surprising, however.

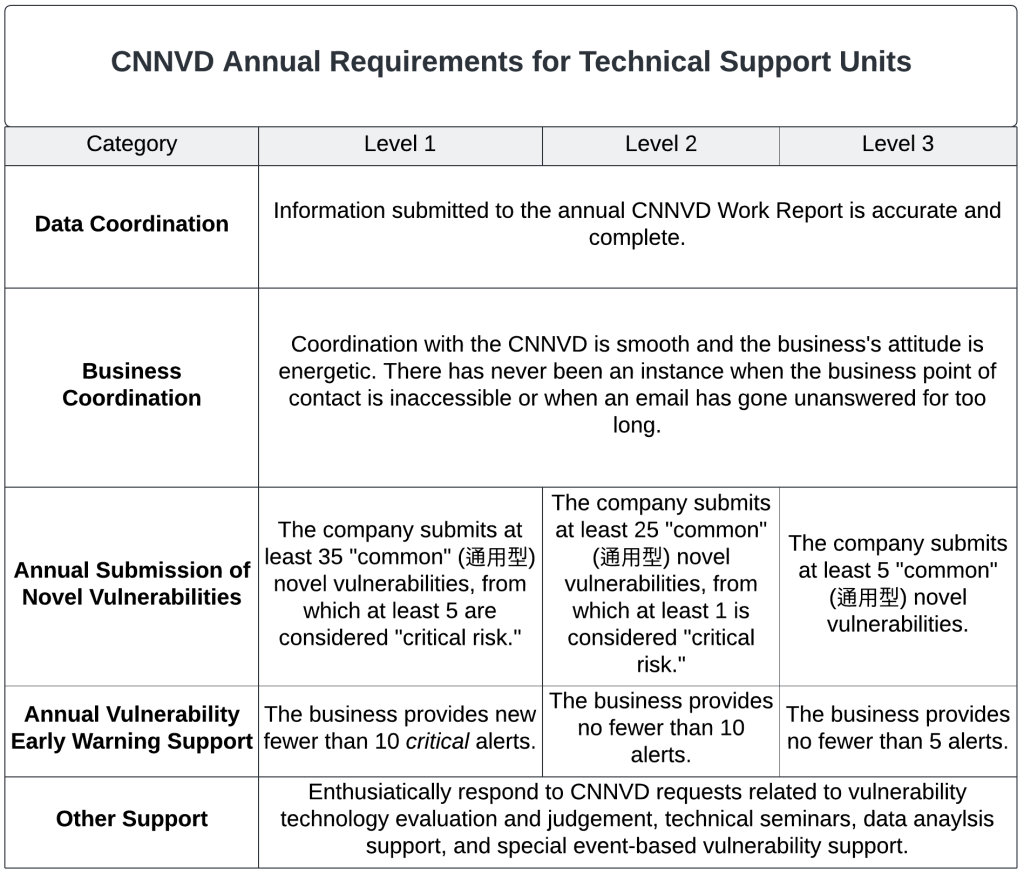

CNNVD technical support units, as the private-sector member companies are called, must meet several requirements. Criteria for tier-one partnership include employing at least twenty software vulnerability researchers, annually submitting at least thirty-five software vulnerabilities—at least five of which are critical according to the CVSS system, responding quickly to CNNVD requests for help or information, and providing early warning of at least ten critical vulnerabilities the company observes being exploited in the wild to the CNNVD. Companies in tiers two and three each have corresponding, though less intensive, requirements. Data on CNNVD’s website do not attribute any vulnerabilities to the firms listed below, instead citing public information. This approach makes it impossible to determine how many vulnerabilities the technical support units supply to the MSS.

Source: CNNVD Handbook, Translation by Dakota Cary

Source: CNNVD Handbook, Translation by Dakota Cary

Based on these requirements, the technical support unit companies employ at least 1,190 researchers dedicated to software vulnerability discovery, and these researchers provide a minimum of 1,955 software vulnerabilities—at least 141 of which are of critical severity—to the MSS each year.

CNNVD’s team of technical support units grew from just fifteen companies in 2016 to 151 companies in 2023. A full list of each tier’s membership is available in Appendix A.

China’s New Vulnerability Management System under the RMSV: the NVDB

The MIIT’s Cybersecurity Threat Intelligence Sharing Platform is operated by the MIIT’s Cybersecurity Management Bureau. The platform also receives oversight from four organizations: China Academy of Information and Communication Technology (CAICT), China ICS CERT (国家工业信息安全发展研究中心), China Software Testing Center (CSTC) (中国软件评测中心), and China Automotive Technology and Research Center (中国汽车技术研究中心). Notably, the China Software Testing Center, a center under the MIIT, works to advance military-civil fusion (likely by testing civilian hardware and software for security vulnerabilities before adoption by the military), is certified by the MSS 13th Bureau as tier 1 for Security Engineering and hosts a “special laboratory” (特种实验室) whose website cannot be accessed. CSTC publishes books on security testing for many kinds of systems, including intelligent manufacturing, smart cars, and ICS systems. CSTC’s website makes clear the center is home to immense software security talent. At the bottom of its homepage, the China Software Testing Center lists the Ministry of State Security as one of its many government customers. It is the only government agency whose name does not also appear in English.

The Cybersecurity Threat Intelligence Sharing Platform includes one organizing platform (the Cybersecurity Threat and Vulnerability Information Sharing Platform; abbreviated NVDB) with five downstream databases. These databases share the same authorization system, and some of the database’s login pages redirect to the NVDB. While each has its own website, some share the same contact information. These findings suggest the five databases are not fully separate from one another, though this may change over time as the bureaucratic structure matures.

The five databases each cover a specific area of technology: general network product devices, industrial-control systems, “innovative information technology” (PRC-made products) used by the government, internet-connected vehicles, and mobile applications. This paper was able to obtain membership lists for four of the five databases. Forty-eight of the 103 companies identified on these membership lists contribute to the MSS-run CNNVD. The full list of companies can be found in Appendix B.

The NVDB does not publish software vulnerabilities, but it shares them with the MPS’ National Cyber and Information Security Information Notification Center and CNCERT/CC (the administrator for CNVD). The Ministry of Public Security conducts offensive hacking on targets within China, suggesting the shared vulnerabilities could be used for law enforcement and surveillance—incident reports could start law-enforcement actions, too.

Access to China’s NVDB is limited to PRC nationals with a Chinese telephone number between 8 a.m. and 8 p.m. Beijing time, so information about the internal functions of the platform is incomplete. However, a “how-to” section of the NVDB website offers information about the platform’s functionality. The resource documents how users can report malicious links, Internet Protocol (IP) addresses, file hashes, and file incident reports—among many other capabilities. The following screenshot shows how users reporting a software vulnerability can indicate the type of vulnerability discovered, and whether the bug is already public.

Other components of the “how-to” page indicate that some vulnerability reports are available to some users. The permissions required to access such reports are unclear. The reports are issued using a custom naming convention, which does not appear to match any other public naming conventions. The reports are deemed sensitive enough that only the example in the first row is not blurred out.

This CSVD vulnerability tag in the first column is only found in one other government procurement document found online. In 2019, CAICT—one of the four organizations that oversees the NVDB—contracted two cybersecurity companies to produce a system now built into the MIIT’s Cybersecurity Threat Intelligence Sharing Platform. LegendSec (网神信息技术) received funding to build a system that would notify users of others’ reports of cybersecurity incidents. EverSec (恒安嘉新)—the company responsible for much of the cloud-computing capabilities at China’s National Cybersecurity Talent and Innovation Base—created a CSVD classification book to automatically validate and score the severity of software vulnerabilities. It is this CSVD scoring-and-tagging system that likely adorns software vulnerabilities submitted to the MIIT databases. The MIIT likely created this new naming convention simply because the use of any other convention (CVE, CNVD, or CNNVD) would require the involvement of an outside organization. A full technical-specifications document for the procurement of the CSVD system is available online.

The NVDB’s downstream databases offer companies support services. The mobile-application database hosts a team that helps companies remediate software vulnerabilities. The tripwires that cause these MIIT groups to help a firm patch its vulnerable software are unclear. This support mechanism aligns well with PRC technology-development policies that aim to improve security. Other researchers have noted how poor IT security is for many PRC tech companies. These remediation services will likely raise the floor of performance.

The MIIT’s supporting role suggests that PRC tech companies are subject to far more in-depth oversight, however occasional, at the software-development level than previously known. This raises questions about how, when, and to what extent the state is involved in a company’s code base, and whether such oversight extends beyond mobile applications and PRC-based companies.

The MIIT’s mission to create new, better technology standards incidentally leads it to fund the discovery of software vulnerabilities in foreign products. For example, the MIIT launched the Internet of Vehicles Identity Authentication and Safety Trust Pilot Project in 2021. CAICT oversees a committee for the project. The pilot project funded at least sixty-one research contracts for improving the security, safety, and trustworthiness of internet-connected vehicles. Qi An Xin, operator of a CNVD partner database mentioned above, hosts the Xingyu Internet of Vehicles Laboratory (星與车联网实验室). Researchers from the lab are likely funded by six of its contracts from the MIIT to improve internet connected vehicles’ security. Researchers shared many of their successful attack methodologies online—some posts include foreign brands, such as Tesla. Researchers submit new vulnerabilities to the MIIT’s Internet Connected Vehicles Vulnerability Database (CAVD)—a subset of the NVDB—as required by the RMSV. Xingyu Lab is even listed among the CAVD’s Vulnerability Analysis Experts Working Group in Appendix B. Some of the vulnerabilities are also reported back to the vehicle’s manufacturer—though these data are patchy and disclosure to the manufacturer is voluntary. Although industrial policy is not the focus of this report, it is clear that some of the MIIT’s other work results in software vulnerabilities reported back to its own databases.

Unfortunately, cooperation with the NVDB by foreign firms appears to be to their detriment. The NVDB’s ICS database lists companies that submit vulnerabilities for their own products. This list includes a handful of foreign firms complying with the PRC regulation. At least one foreign firm submitting to the database said it was not receiving reciprocal reports of vulnerabilities in its own products found by other researchers, while, at the same time, it saw a significant decrease in vulnerabilities reported from China. In effect, this company lost visibility into vulnerability research published in China, and was simultaneously submitting its own internally discovered bugs to the MIIT without any benefit to the firm besides RMSV compliance. This anecdotal evidence supports the analysis in the CNVD section above regarding missing ICS vulnerabilities. It is unclear whether the firm is proactively submitting its vulnerabilities to other governments.

Few good options

In contrast to China’s vulnerability collection system, the United States’ disclosure system seems less organized, and its voluntary nature makes the government’s aperture smaller.

In the United States, software vulnerabilities are issued a Common Vulnerabilities and Exposure (CVE) ID by a MITRE-approved CVE Numbering Authority. When one of the nearly three hundred CVE Numbering Authorities—ranging from cybersecurity firms to device manufacturers—issues a CVE, the vulnerability is automatically connected to the National Vulnerability Database run by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Software vulnerabilities can, thus, be reported to any number of companies, at any time the researcher chooses, for compensation or for free, before the CVE Numbering Authority verifies the vulnerability and issues a CVE, thus making the vulnerability public. Like China’s MIIT, CISA also offers services to support vulnerability patching and mitigation. Most significantly, there are no means to compel companies or researchers to submit vulnerabilities to CVE Numbering Authorities—regardless of whether they participate in China’s system.

Policymakers’ instinct may be to copy some parts of China’s system—say, requiring that firms that provide vulnerability information to China’s government also provide it to CISA. These types of reforms are unnecessary and, ultimately, useless. Nothing is gained if companies are required to submit vulnerabilities to CISA when they submit to the MIIT. The US government does not have the remit, nor capability, to defend private computer networks. The short amount of time between vulnerabilities being reported and patched—just nine days in 2018–2019 according to Mandiant (now part of Google Cloud)—emphasizes the limited value of collection for defensive purposes. Without the ability or time to operationalize knowledge about vulnerabilities reported to the PRC for defensive purposes, mandating they be reported to CISA has no clear value.

The lack of value in policy changes to the US system for defensive purposes raises questions about China’s own motives.

The time between vulnerability discovery and patching in China is unknown. It may well be longer than the nine days suggested by Mandiant data on US-issued CVEs (which includes US and many foreign products), but this discounts the considerable talent employed at China’s leading technology companies. Companies may not be prioritizing vulnerability remediation at the pace policymakers prefer, but—in a tech sector with a twelve-hour workday, a six-days-per-week work culture, and significant state emphasis on security—it seems unlikely. Surely the Chinese researchers who dominated Pwn2Own and other international vulnerability competitions before they were blocked from leaving the country are still quite good, and are able to secure companies’ products in China.

However, the MIIT’s Cybersecurity Threat and Vulnerability Information Sharing Platform, which operates the NVDB, likely improves China’s collective cyber-defense capabilities in a different way. Rather than instigating firms to patch known vulnerabilities, the NVDB likely improves cybersecurity companies’ ability to detect cyberattacks by increasing visibility of known vulnerabilities. If cybersecurity firms can access all vulnerability reports submitted into the database—which this report cannot confirm—then the result would be improved cybersecurity. Companies could take these reports and integrate them into their operations, creating new detection rules that make exploiting the vulnerabilities harder even before a patch is available.

This system would offer significant defensive advantages over the US ecosystem. Currently, cybersecurity companies become aware of software vulnerabilities when they are given a CVE by a CVE Numbering Authority, or when the company observes the zero-day vulnerability being exploited on its customer’s systems. This process creates a dynamic in which cybersecurity companies can only defend against what they have observed as a company. Firms with more customers have greater visibility and, if efficient, detect more vulnerabilities being exploited before they are issued CVEs. Mandiant was able to produce its report on the timeline of vulnerability patching precisely because of its visibility into attacks against its customers.

What to do? Creating a database like the one operated by the MIIT could erode cybersecurity companies’ competitive advantages over one another. Hard-fought market share, keen threat intelligence, competitive pricing, and satisfied customers allow companies to compete in the market. Forcing the aggregation of these companies’ data on software vulnerabilities being exploited and intrusions against customers (as the MIIT’s NVDB collects) would significantly upend the cybersecurity market. Besides upsetting the market, creating a shared database of vulnerabilities and intrusions against customers would also create a significant target for foreign intelligence services. The data it held would be valuable counterintelligence information—letting foreign governments know which operations are being tracked by defenders.

A better path would be for policymakers to implore CVE Numbering Authorities to verify vulnerabilities and assign them a CVE quicker. This would push reported vulnerabilities into the public view, and allow for all firms to update defenses without compromising the privacy of their customers or creating a target for intelligence collection. A public leaderboard of all CVE Numbering Authorities with each organization’s average time to complete validation and naming of vulnerabilities could instigate progress. Although a negative externality of this progress may be an increase in vulnerabilities for attackers to exploit (data do show many hackers quickly target vulnerabilities after they are published or after a patch has been released), the spike might be short lived. Companies would need to respond to the pressure of public disclosure by ramping up efforts to patch software—a positive outcome for everyone.

Conclusion

After changes to policy in 2017, cybersecurity researchers from China were prohibited from traveling abroad to participate in software security competitions. The new rules aligned with China’s thought leaders at the time. The prevailing idea that such vulnerabilities are a “national resource” remains unchanged. China then took steps to set up its own software vulnerability competitions, such as Tianfu Cup. The competition has attracted attention for the number and quality of vulnerabilities furnished by researchers each year. Also in 2017, China began hosting competitions to spur progress on technologies to automate the discovery, patching, and exploitation of software vulnerabilities. This system, however, did not allow the state to collect all vulnerabilities discovered in China. The security services were still only receiving voluntary reports from companies electing to participate in their databases. CNVD seemingly attempted to improve collection by adding its partner databases from higher education and the private sector, but this was only a half measure.

China’s system for collecting software vulnerabilities is now all encompassing. The PRC system has evolved from incentivizing voluntary disclosure to security services and encouraging disclosure to private-sector firms into mandating vulnerability disclosure to the state.

The 2021 RMSV increased the aperture of China’s vulnerability collection. Companies doing business in China are required to submit notice of a software vulnerability within forty-eight hours of being notified of it. Our report shows at least some foreign firms are complying with the regulations—though our limited visibility likely deflates the true number of companies adhering to the rules. Independent researchers, while not expressly required to disclose vulnerabilities to the MIIT, are prohibited from publishing information about vulnerabilities except to the company that owns the product—the same companies required to report the vulnerability to the government. The result is near total collection of software vulnerabilities discovered in China.

Researchers and organizations are now subject to dual reporting structures—mandatory disclosure to NVDB and continued, voluntary disclosure to CNVD or, in the case of technology support units, submission thresholds to meet membership requirements for the MSS CNNVD. A graphic from the “about us” section of the NVDB encourages reporting to the old CNVD and CNNVD databases concurrently. Indeed, many of the CNNVD technology support units are also listed on the MIIT databases’ respective membership lists. The parallel existence of these databases and competition between legal requirements to submit into the new system and incentives to voluntary disclosure into the old systems suggests some squabbling over turf between bureaucracies. For the companies involved in multiple databases, there is a clear incentive to act as an intermediary across bureaucratic boundaries.

This report demonstrates that the mandated vulnerability and threat-intelligence sharing from the MIIT’s new database to the CNCERT/CC’s CNVD facilitates access to reporting by a regional MSS office, a known PLA contractor, and a university research center with ties to PLA hacking campaigns and which conducts offensive and defense research. These organizations with ties to offensive hacking activities would be negligent if they did not utilize their access to CNVD vulnerability reports to equip their operators. The observable increase in the number of zero-days used by PRC hacking teams, as indicated by the 2022 Microsoft “Digital Defense Report,” suggests that these organizations’ access is resulting in vulnerabilities being used by offensive teams.

Other countries’ security services often rely on their own tools to discover, purchase, and observe software vulnerabilities for offense and defense. China’s security services do all of those things, too, but the new pipeline established by the RMSV provides it a clear advantage in accessing software vulnerabilities discovered by the private sector.

Key recommendations

- Policymakers should seek to decrease the time between software vulnerability report submissions to CVE Numbering Authorities and the time it takes for them to be validated, named, and published. Efforts to recreate China’s system in the United States would not succeed in any meaningful sense, and would likely be met with opposition by industry. Instead, improving industry performance within the current system is the best approach. Many of the approximately 300 CVE Numbering Authorities are companies with their own products. Vulnerabilities in products from companies that are not numbering authorities are slower to be validated and published. This creates a bottleneck of unverified and unvalidated vulnerabilities.

- Policymakers should seek to improve US government vulnerability intelligence. Vulnerability intelligence uses the precursors to vulnerability discovery—namely, the people, companies and organizations, their technical competencies and niches, the tools and kit they purchase, and any vulnerabilities they make public—to estimate who might be working to discover vulnerabilities and in which systems. Crucially, this research would create insights into the kinds of vulnerabilities that foreign researchers are discovering, but not publishing. Data found in this report, such as lists of companies in the appendices, could be used to enable further research and collection on this topic.

Editors: Chris Rohlf, Kitsch Liao, Colleen Cottle, Winnona DeSombre, Jonathan Reiter, Stewart Scott, Devin Thorne, and Ian Roos.

Appendix A

Appendix B

Technology Member List

Product Member List

Technology Support Units

Vulnerability Analysis Experts Working Group

Technology Support Units

Related content

Image: A map of China is seen through a magnifying glass on a computer screen showing binary digits in Singapore in this January 2, 2014 photo illustration. Picture taken January 2, 2014. REUTERS/Edgar Su (SINGAPORE – Tags: SCIENCE TECHNOLOGY BUSINESS TELECOMS TPX IMAGES OF THE DAY) – RTX174Q6