Highlights :

- As Solar Capacity Ramps Up In India, Recycling Emerges On The Horizon As a Critical Need.

India Gears Up For Solar Waste Recycling Challenge

The latest report from the Central Electricity Authority (CEA) states that India’s total solar energy capacity crossed 75 Gigawatts (GW) by the end of February this year. According to its own estimates, the country will need 292 GW of total solar capacity by 2030.

With the steady additions of solar power to the Indian grid, the South Asian country is also adding something that it would not like to cherish– a million tonnes of anticipated solar waste. Linked directly to the total projected lifetime of most solar installations at 25 years, the waste issue is likely to be accelerated by the premature retirement of many modules to be replaced with higher efficiency modules in time. The global solar recycling market, estimated at just around $250 million this year, is expected to grow to be a $2 billion plus market in very quick time, perhaps as early as 2032, depending on price movements in critical minerals used.

The heightened pace of solar deployments worldwide and in India certainly point to a market that will be vital to burnishing solar’s green credentials in the next few years.

Jan Clyncke

This volume of waste set to be generated at the end of their lives will be further augmented due to damage owing to extreme weather events, transportation, manufacturing, or other sources. Jan Clyncke, Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of PV Cycle, a European not-for-profit venture involved in solar module recycling globally, told Saur Energy even the 73 GW of solar capacity alone could lead to the generation of a massive 4.5 million tonnes of solar waste. This quantum of solar PV is likely to be a reality at the end of their lives.

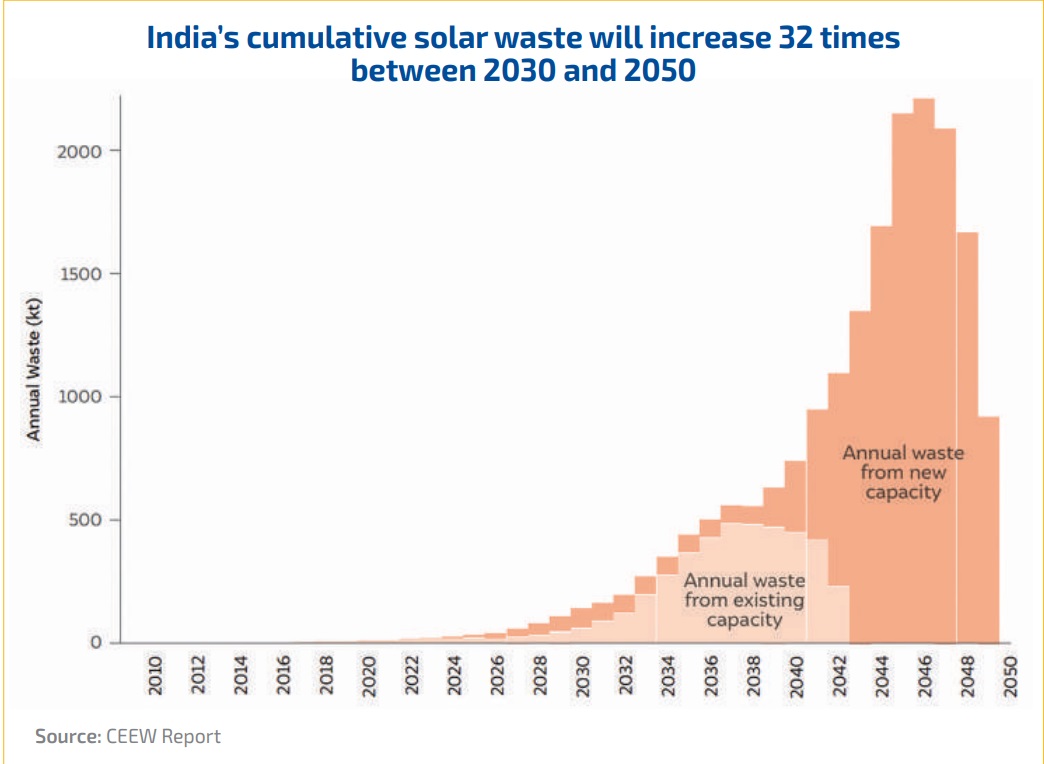

New Delhi–based think tank, the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW), recently released a report on solar waste on March 20 this year. The report said that India’s installed 66.7 GW capacity, as of FY23, generated about 100 kilotonnes (kt) of waste, which will increase to 340 kt by 2030. It also said that India’s cumulative solar waste will increase 32 times between 2030 and 2050, hinting at the scale of waste created by the renewable energy source.

The report also said that around 67 percent of this waste is expected to be generated in five renewable-rich states of India–Rajasthan, Gujarat, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu. Before CEEW, IRENA (International Renewable Energy Agency), NSEFI (National Solar Energy Federation of India) and CSTEP also came up with their own projections of the likely generation of solar waste in India under different circumstances.

Solar Waste & Challenges

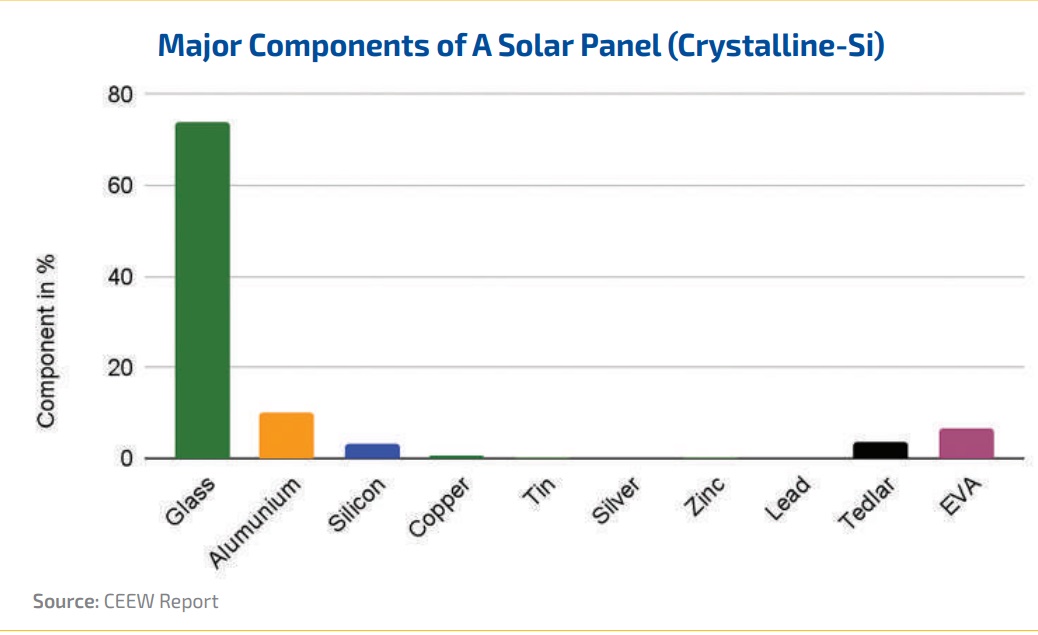

Unlike other sources of waste with little economic value attached, new age green materials like discarded solar panels or solar waste possess several items of economic value, including critical minerals like Silicon, Copper, and others, as well as other components used to make solar panels. In this, they join another key component of the green transition, Lithium Ion batteries. But where Lithium batteries are already looking at recycling levels of over 95%, solar modules have some way to go.A solar PV module (crystalline silicon) primarily comprises Glass (around 74%). Other items include Aluminum, Silicon, Copper, Tin, Silver, Zinc, Lead, Tedlar (back sheet), and Encapsulant. As per the Critical Mineral List of the Indian Ministry of Mines, components like Silicon, Copper, Tellurium, and Cadmium are considered critical minerals.

The sector is currently witnessing several challenges, ranging from the large involvement of the informal sector to technological and infrastructural hurdles, funding, awareness, and much more. This is in addition to the lack of authentic data, monitoring, and regulation of the whole sector in the absence of stringent rules and regulations for the sector.

Akanksha Tyagi

Akanksha Tyagi, Co-author of the latest CEEW report on solar waste and Programme Lead at the organisation, told Saur Energy that limited efficient recycling technologies that are able to recover all module components at the highest purity grades are a challenge, which can be addressed by expediting technological innovations.

She said incentives for recycling when the economics are unfavourable would help recyclers initiate solar module recycling. “Additionally, there is a need to address the low economy of scale for solar waste recycling by demand aggregation from various sources. Aggregating the waste modules shall help to achieve the critical mass. This will improve the economics for pilot demonstrations and thereby generate India-specific data on waste management parameters. Here, the manufacturers can combine efforts to collect waste and channel it to recyclers to achieve manageable volumes,” Tyagi told Saur Energy.

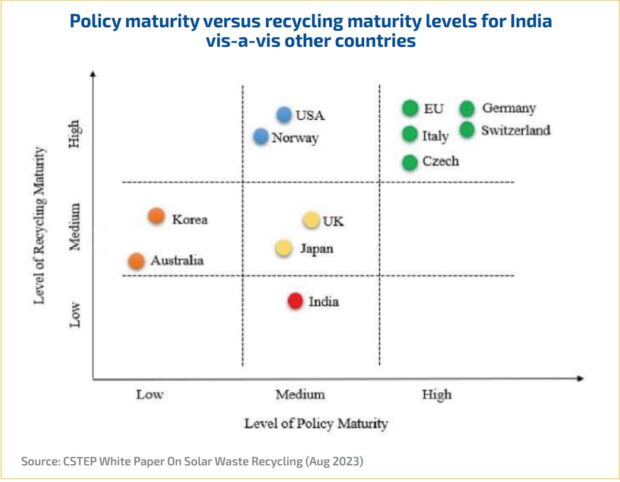

India’s Policy Preparedness

Globally, the European Union (EU) seems to be one of the pioneers in taking concrete steps towards planning to focus on recycling solar waste. In 2012, the EU developed a legislation–Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE). The law mandates collecting and treating end-of-life solar modules and their recycling. It also puts the onus on solar module manufacturers, importers, and rebranders to comply with these rules with its Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) provisions.

The Indian government has also started taking steps in this direction. In 2022, the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) submitted its detailed report on the circular economy in solar panels to the NITI Aayog. The same year, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) released its E-Waste Management Rules 2022, which included solar PV modules and cells under its ambit. These rules came into effect on April 1, 2023.

The rules mandate that solar module manufacturers and recyclers register with a central portal of the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) and file their annual returns. The module makers were also asked to store solar module or cell waste generated upto 2034-35 These rules also asked the module makers to put the details of the inventory of their solar modules or cells on the portal.

As per MoEFCC, India will get its first-ever detailed report from the solar module makers on their total module sales and replacement by the end of June this year. This is likely to bridge the data gap for the sector at the national and granular levels.

“Soon, the Central Pollution Control Board’s portal for Electronic waste (EPR) will provide data on annual module sales and modules replaced. It remains to be seen if this data will be available for the public or only for registered entities. However, this data will be presented at an aggregated level (for a solar cell/module producer), so we need more granular data like the data on how many modules are being replaced and for which activity under each project (commissioned/under construction),” CEEW’s Tyagi added.

These e-waste rules of 2022, however, have put the onus on the solar module manufacturers for the scientific disposal and management of the solar waste they created. However, little detail and a lack of a clear pathway for solar waste recycling remain absent. A senior official from the MoEFCC said that until now, the ministry has not put the liability of EPR targets for solar module manufacturers under the e-waste rules as there is not enough solar waste available for recycling and it will take some time to make the solar recycling business a viable business model.

Bangalore-based think tank Center for Study of Science, Technology and Policy (CSTEP) published a white paper last year on solar recycling. The research paper, which studied several norms, standards, and laws globally, said that more provisions were needed in the policy to boost the circular economy in the solar industry in India.

Anjali Taneja

Anjali Taneja, Senior Policy Specialist leading the Sustainability vertical at CSTEP and the author of the white paper, told Saur Energy, “While the handling of photovoltaic (PV) waste has been brought under the e-waste guidelines, what could perhaps be considered more effective is to have a special provision for PV waste under the e-waste guidelines to segregate PV waste management from the overall e-waste handling.”

She also added, “Our research, which also included a series of stakeholder consultations, found that having certain mechanisms such as recycling benchmarks, regulation of a waste disposal fee, a waste monitoring and tracking system, and continuous engagements between the government, industry, and civil society could prove to be beneficial for a comprehensive solar waste recycling policy.”

Industry preparedness

Sujoy Ghosh

The solar industry is also slowly preparing to pave the way for more scientific recycling of solar panels so that they can either be reused as solar panels again or the extracted components of economic importance could be used in some industries.

For example, global solar module manufacturer First Solar sends the extracted polyolefins from the modules to be used to produce footwear. It also re-uses the CdTeSe semiconductor material extracted from EOL (end of life) modules in manufacturing new modules.

Sujoy Ghosh, Country Managing Director (India) of First Solar, said that to make the recycling business more viable, the industry needs to diversify the end use of the extracted items from the solar panels because reusing glass for new solar panels would be challenging and a costlier affair. He also said that refurbishing older solar panels would not be attractive for the solar market in the future.

“I do not believe refurbishing solar panels for the future would be a good idea from a technology point of view because, with time, technologies are becoming more efficient, thereby lowering the cost/watt produced for new modules So, refurbished modules with low efficiency polycrystalline may not be competitive against new modules,” Ghosh said.

Ghosh also talked about the costs involved in solar cycling globally. He said the current regulated solar panel recycling fee is around 1.63 Euros per module in France, excluding cost of logistics. He said that in the overall recycling value chain logistics account for 50-60%

Additional cost dilemma

Navitas Solar is a Surat-based solar module manufacturer. It has collaborated with Green World Sourcing Solutions for waste disposal. This local e-waste aggregator takes solar waste from the firm and supplies it to another recycling firm.

Vineet Mittal, Co-Founder at Navitas Solar, told Saur Energy that there are a lot of issues concerned with the additional cost burden for solar module manufacturers when it comes to solar module recycling. He said that the new segment puts the onus on the module makers. Mittal said that financing solar recycling needed a well-thought-out strategy that could allay the fears of Indian solar makers over the additional burden beyond manufacturing modules.

“Several solar cells and modules are still imported from countries like China to India. I believe if more policies towards these are made, special focus should be given to allow a level playing field for Indian solar module makers. The total responsibility for its recycling to Indian module makers may put an extra financial burden on them. This could be negated with some government-initiated reforms like imposing additional tax or cess in imports of modules in India to take care of the extra financial burden for recycling,” Mittal told Saur Energy.

Mirunalini Chellapan, Director of Swelect Energy Systems, another Indian solar module maker, suggests that the additional finances for solar recycling could also be taken care of by imposing a cess or tax in ‘frontloading’ when the modules are sold to the developers. She said the tax component imposed at this trading level can negate the additional financial burden.

Mirunalini Chellapan

She also suggested other ways to boost the circularity of solar modules in India. She told Saur Energy, “First of all, solar waste should be treated differently from e-waste, and a separate category of renewable waste should be created. Second, dumping solar modules in landfills should be strictly penalised. Thirdly, the government can also count on the recycling cost and mention it in their tenders to take care of the segment from the initial phase itself in large government projects.”

Prashanth Mathur, CEO of Saatvik Solar told Saur Energy that all solar panels do not become a waste product till the end of their lives, but some, either due to damage or low efficiency, get replaced even in below the period, leading to premature solar waste generation.

He also raised the issue of the need to focus on the financials for solar recycling: “Somebody has to pay for this. This could come either in the form of an incentive, tax, cess, or something else. Maybe we can make such an arrangement where the consumer can also pay if such arrangements are made in the trade system.”

Mathur said that his firm has already started working with European firm PV Cycle to ensure the recycling of its solar waste. “We started working with them for the last three years. Under the arrangement, they take the waste and manage it with their expertise at their end. We did it voluntarily to shift our focus towards circularity.”

Prashant Mathur

Due to the anticipation of a lower scale of solar waste in India, recycling systems have mostly remained on a pilot scale. For example, the Maharashtra Institute of Technology – World Peace University, Pune experimented with using crushed solar panels as a replacement for sand for use with concrete in building construction as part of a pilot project. Experts claim that opportunities do exist in the recycling segment in India, too, but they demand a focus on research and development.

“Finance-related challenges in the recycling of solar panel waste could be sorted through better incentives and schemes for investment-building and research and development by leveraging public–private partnerships and perhaps by offering attractive pricing mechanisms for manufacturers and producers handling PV waste. Moreover, market-based schemes to encourage the start-up industry in PV waste management could prove to be beneficial. In other words, a conducive business environment and various support mechanisms can help alleviate financial barriers, particularly during the initial phases. When managing end-of-life (EoL) waste,” CSTEP’s Anjali Taneja added.

PV Cycle, a European firm, works as a Producer Responsibility Organization (PRO) involved in collection, monitoring and auditing. It has collaborated with several Indian firms, too.

Jan Clyncke, CEO of PY Cycle, told Saur Energy that there is no technical dearth for recycling of solar waste but the problem mainly lies currently on the scale of supply of solar waste, which can decide on the fate of new recycling firms and their business models.

When asked about the important parameters that could be part of any policy in India towards solar recycling, Jan said, “It should have standards for collection and targets which can bolster the confidence of new firms who want to join the recycling industry with some innovative ideas.”

A senior official from the MNRE told Saur Energy that MoEFCC is likely to develop a new policy framework for solar module recycling by 2024. MNRE is also holding talks with different stakeholders on the issue and may come up with some offerings anytime after 2024.

Conclusion

While the Indian government has taken steps to start framing policies, many questions remain unanswered for the Indian solar module makers. Some of these include clarity on the fate of solar panels if the solar module firm suffers insolvency before the end of their lives and the fate of modules used in projects that saw acquisitions or witnessed equity transfers.

Financing is another major concern for solar module makers, and they need clarity to plan their roadmap. On the other hand, many e-waste and other recyclers in the country have also explored opportunities in the sector. They are waiting for clear answers, technology and support to jump onto the bandwagon. A more clear-cut, target-based, tailor-made solar recycling for India is needed when India is emerging as one of the major solar market leaders globally. What is clear is that whatever be the policy, the economics of the business mean that multiple sites close to major installation clusters will be needed, along with incentives as well as a compliance framework that ensures that the country is ready for the first wave of discarded panels that will start building up from 2030 or before.