Manoj Sinha, CEO and Co-Founder

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), India is “one of the largest electrification success stories in history”, accounting for two of every five people newly electrified since 2000. The proportion of India’s population with access to electricity grew from 68% in 2010 to over 99% in 2019. But the reality on the ground is much different from what’s reported. For most rural Indians, the power supply from state-owned utilities (known as Discoms) is unreliable and of poor quality, which is stifling growth in an economy that relies on more than 41% of employment from agriculture. At the same time, the government appears to have finally lost its patience after multiple Discom bailouts and, in late 2020, indicated that it would push forward with more aggressive plans to open electricity distribution to the private sector.

This dynamic, combined with India being on “the cusp of a solar-powered revolution“, has created an opening for a new grid technology: the mini-grid.

Incorporating mini-grid technology offers a massive opportunity in rural India since, based on a Smart Power India (SPI) report, only 65% of enterprises have grid-electricity connections. The SPI report also highlighted that one in two grid-users faces power cuts for at least 8 hours every day. Conversely, over 80% of mini-grid users indicate satisfaction with their electricity connections; mini-grids also provide more reliable and higher-quality power to households and micro-enterprises in rural regions. These contributing factors and high Discom connection costs are giving mini-grids an opportunity to overcome existing barriers to electricity adoption and enable local small businesses to fuel sustainable economic growth. Mini-grid battery storage can also help stabilise the national grid, as over 400 GW of solar and wind power are expected to come online.

One company, Husk Power, has emerged as the market leader in mini-grid technology and recently announced two industry milestones — over 100 community mini-grids built in Asia and Africa and more than 5,000 small business customers currently served. In India alone, Husk Power mini-grids have a capacity of over 5 MW. Through its hybrid solar PV and biomass generators, local enterprises — carpentry shops, shopping centres, rice mills, welding shops — as well as schools, hospitals and homes have been able to access electricity 24/7 in the Indian states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, where a high frequency of power cuts is common due to deficits in the power supply.

MORE FOR YOU

Intelligently powering villages with locally produced renewable energy

For Indian native, Manoj Sinha, CEO at Husk Power, delivering affordable, reliable and clean electricity to rural villages has been the core motivation behind Husk’s mini-grid technology, which locally produces 100% zero-carbon electricity from biomass, battery storage and solar power systems. In the past year, Husk Power has managed to scale its operations despite the economic slowdown and lockdown measures. In March 2020, India’s sudden announcement of a national lockdown resulted in a mass exodus of migrant workers from urban centres to their homes in rural villages. According to the World Bank, the rural-urban migration impacted nearly 40 million people, with many being driven by economic necessity and the growing uncertainty in cities. As migrant workers began to resettle in the countryside, the need to provide reliable energy became even more critical in keeping essential rural services such as hospitals, grocery stores and pharmacies open and powering small businesses and farmers to drive the local economy. In an interview, Sinha said that the “growing demand to supply power to rural communities in recent months has allowed Husk to demonstrate the resiliency of its mini-grids system”.

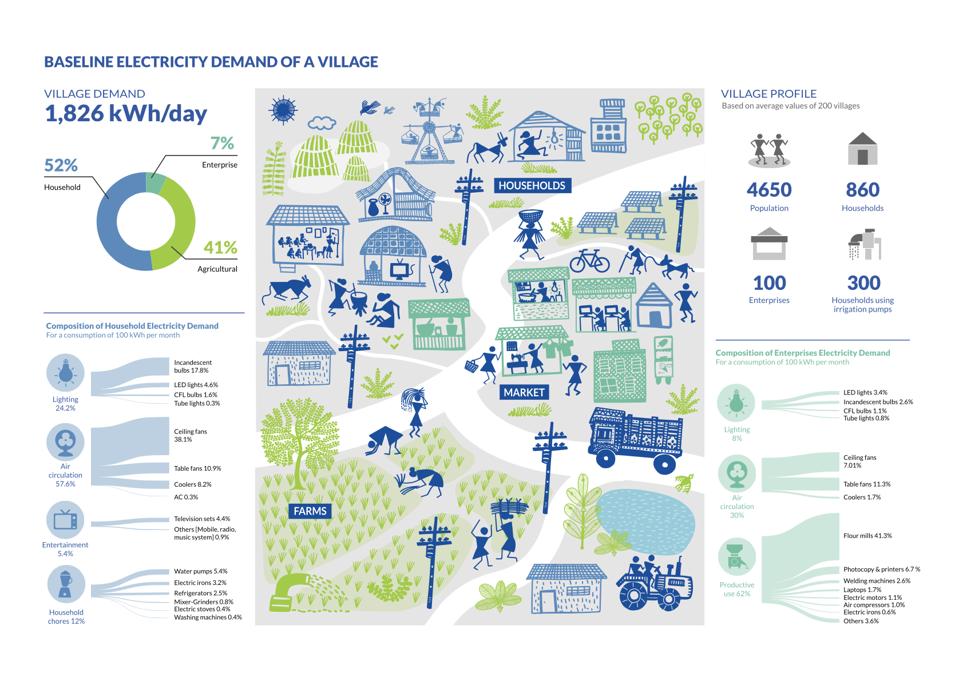

Baseline electricity demand of a village in India

By using smart-prepaid meters, Husk’s real-time demand management system has developed energy profiles of its customers to supply cost-effective and reliable power that optimises the use of biomass, battery storage and solar power during the day. Sinha highlighted that Husk’s control rooms aggregate the data from their customers’ energy profiles to build artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms that intelligently forecast demand. Based on the projected energy demand in the village, Husk’s control room distributes the cheapest power source to their customers — solar energy during peak demand in the day and then biomass and battery during the night — and also to minimise their overall costs. To manage the village’s long-term power demand, Husk has also taken measures to build services that improve energy efficiency and ensure a reliable power supply. Sinha mentioned that Husk has developed an e-commerce platform that gives customers the option to “purchase energy-efficient electrical appliances such as LED TVs, ceiling fans, refrigerators and freezers to help manage their power demand more efficiently”. For the local micro-enterprises, Sinha added that the demand for electrical appliances through their e-commerce platform also helps stimulate growth in the local economy because the “local shops in the village act as fulfilment centres and pick up points for the end consumers.” Husk also offers financing for purchasing machines that enables customers to increase productivity by up to 10 times.

Enabling farmers, households and hospitals to access cost-effective power

As the lockdown measures took place in India, many of Husk’s rural customers faced income shortfalls from the closure of non-essential shops and services. To address these challenges, Husk implemented a 50% power discount program for all businesses and developed irrigation and water purification services to ensure farmers keep up production and households have access to clean water supply. By implementing these programs and initiatives, Husk was able to provide direct support to the villages, which helped grow their “customer base by 52% and revenue by 101% from March 2020 to September 2020,” Sinha said. He also highlighted how the pandemic allowed Husk to understand their customer base and develop more customised solutions to ensure their daily needs are met. For example, farmers are a key customer segment and regularly need to irrigate their land to keep up food production. To optimise farmers’ costs, Sinha said Husk’s control system would coordinate with them and irrigate their land by redirecting power supply from the mini-grid during non-peak hours to keep power costs down.

For households, another key customer segment, Husk has also taken similar measures by purifying water during non-peak demand that allows villagers to purchase clean drinking water from a nearby facility at a low cost. As of 2018, only 18.2% of rural households had piped water supply, with the current rate of progress lagging behind the government’s target of universal access to safe drinking water by 2024. Due to the need for drinking water, Sinha said that Husk used their facilities to build water purification centres so that households could cook their daily meals from products supplied by the farmers in the villages who were also receiving irrigation support from Husk. Through these end-to-end measures, Sinha noted that Husk has supported local communities and allowed them to self-manage their livelihoods in rural India. Alongside addressing food security, Sinha also mentioned that Husk’s control system had maintained priority power supply to hospitals in the villages. He said that since the power supply is crucial for hospitals, Husk’s control system has been designed to intelligently manage the power supply and ensure that their power distribution is optimally operating within the mini-grid system.

Aiming to become India’s largest rural utility company

Last-mile connectivity plays a critical role in the adoption of power in rural India. Although India’s Discoms have made strides in improving their last-mile service in these regions, a new SPI study found that 40% of rural consumers are dissatisfied with the state grid. The study recommended that energy service providers operating in rural regions adopt a customer-first approach and improve their reliability and quality of supply. More recently, a Rockefeller Foundation-led survey also noted a similar figure, with just 37% of rural customers being satisfied with their utility’s overall services. Given the challenge for Discoms, Sinha said that Husk’s “customer-centric approach allows them to provide high quality and highly reliable power to villages and better serve the needs of the rural population with customised solutions.” According to the World Bank, the development of mini-grids and integrating them into the main grid in the future provide a unique opportunity to leverage the energy assets of the main grid and the high-touch solutions of mini-grids.

On the commercial opportunities to integrate Husk’s mini-grid with India’s Discoms, Sinha said that their “technology is ready for integration and such collaboration would positively change the energy service delivery landscape to rural customers.” To prove the concept, Husk is developing a pilot program that would involve Husk’s mini-grids partnering with the national grid in Nigeria. As Nigeria’s Electricity Regulatory Commission Mini-Grid Regulation 2016 provides a blueprint in the event the main grid reaches isolated mini-grids, Sinha said Husk aims to use the Nigerian policy blueprint to “prove their technical capabilities and demonstrate the ability for the two grid systems to buy and sell power.” Based on the results, Sinha hopes to build upon the pilot projects and develop strategic partnerships with India’s Discoms that would allow Husk to integrate with large utilities and improve last-mile power distribution in rural India.