The world’s software supply chain today is no longer a physical channel but an electronic network. Amazon is the last half-century’s greatest innovator of supply chains. To say Amazon.com disrupted the tech industry is like saying The Beatles brought a nice change of pace to music. Amazon did disrupt tech, certainly, but that was step one. It then played a principal role in rebuilding information technology, and reorienting its centers of power. Now, we no longer obsess about Microsoft, Microsoft, Microsoft, mainly because Jeff Bezos and Amazon had a damn good idea.

When a computing service is made available to you anywhere in the world through the Web, on servers whose functions have been leased by a publisher, software producer, or other private customer, at the end of 2020, there was a 32% chance (according to analyst firm Synergy Research Group) that this service is being hosted on Amazon’s cloud. By comparison, there was a 20% chance that it’s hosted on Microsoft’s Azure cloud, and only 9% on Google Cloud Platform.

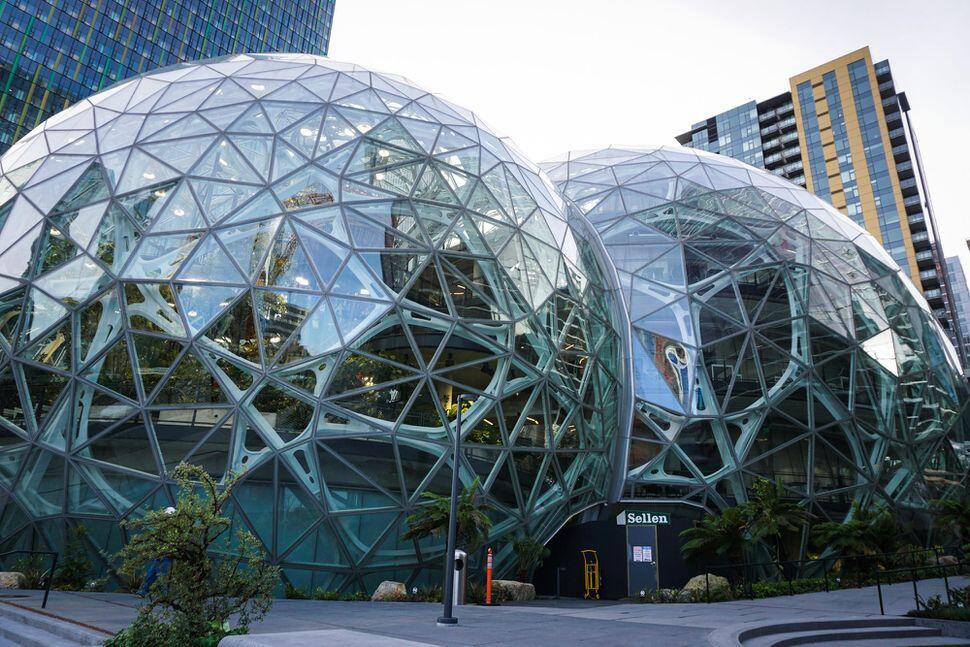

Amazon is the company most associated with “the cloud,” in the minds of the general public. It also happens to be the world’s largest e-retailer. Today, Amazon Web Services (AWS) is the world’s largest provider of computing services accessible through the Web, from globally distributed servers in highly automated data centers.

LEARN MORE:

What Amazon AWS does, generally speaking

Astonishingly, Amazon as a corporation presents its own cloud business, Amazon Web Services (AWS), as a subsidiary entity — a venture on the side. In over 4,500 words of written testimony submitted by Amazon’s then-CEO Bezos in July 2020 to the House Antitrust Subcommittee [PDF], ostensibly about the potentially overbearing and heavy-handed role that Amazon, Google, Facebook, and Apple play in directing the course of technology, the word “cloud” appears but twice.

Bezos, who is planning a transition to Executive Chairman of the company in Q3 2021, shouldn’t have anything to hide. AWS is a major contributor to the American economy in several significant respects (one notable exception being federal taxes), partly due to its being bonded to a company with colossal revenue from e-commerce. In February, veteran financial analyst Justin Fox estimated that, in 2020, AWS invested close to two-thirds of its annual technology expenditure into its own research and development efforts — some $26.7 billion, by Fox’s calculations. That would make research projects alone a measurable component of the nation’s gross domestic product, the sudden absence of which would trigger an economic meltdown.

LEARN MORE:

How Amazon got to this point

Amazon Web Services, as was evident from the division’s original name, enables Web sites to be hosted remotely. Since its inception, though, AWS has grown into the world’s principal provider of virtual infrastructure — the operating systems, hypervisors, service orchestrators, monitoring functions, and support systems upon which the economy of the public cloud is based.

Jeff Bezos explained his company’s basic philosophy in clear and indisputable terms, in a 2010 letter to company shareholders:

…While many of our systems are based on the latest in computer science research, this often hasn’t been sufficient: Our architects and engineers have had to advance research in directions that no academic had yet taken. Many of the problems we face have no textbook solutions, and so we — happily — invent new approaches. Our technologies are almost exclusively implemented as services: bits of logic that encapsulate the data they operate on and provide hardened interfaces as the only way to access their functionality. This approach reduces side effects and allows services to evolve at their own pace without impacting the other components of the overall system.

Bezos likes to adorn his biographical presentations with veritable fountains of fabulous phrases, along with boasts that may warrant a bit of suspicion. For example, in this letter, he gave AWS credit for essentially inventing service-oriented architecture (SOA) — he was, at best, a teenager when SOA was first being put to practical use. So let’s try to explain what this AWS thing does, in terms even a CEO could understand.

AWS’ principal innovation was commoditizing software services

Up until the mid-2000s, software was a thing you installed on your hard drive. It was intellectual property that you were granted the license to use, and either the entirety of that license was paid for up front, or it was subscribed to on an annual “per-seat” basis. A corporate network (a LAN) introduced the astounding technical innovation of moving that hard drive into a room full of other hard drives; otherwise, the principal idea was not much different. (Microsoft thrived in this market.)

The first truly brilliant idea that ever happened in corporate LANs was this: An entire computer, including its processor and installed devices, could be rendered as software. Sure, this software would still run on hardware, but being rendered as software made it expendable if something went irreparably wrong. You simply restored a backup copy of the software, and resumed. This was the first virtual machine (VM).

The first general purpose for which people used VMs, was to host Web sites. There were plenty of Web site hosts in 2006, but they were typically blogs. Prior to the rise of the cloud, when an organization needed to run its business online using software that belonged to it, it would install Web server software (usually Apache) on its own physical computers, and connect them to the Internet via a service provider. If a business could install a Web server on a virtual machine, it could attain the freedom to run those Web servers anywhere it was practical to do so, rather than from the headquarters basement. The first great convenience that cloud-based VMs made available, even before Amazon officially launched AWS, was to enable organizations (usually e-commerce retailers) to set up their own service configurations, but run them on Amazon’s infrastructure.

Once Amazon had a cadre of e-commerce customers, it established its first cloud business model around making its infrastructure available on a pay-as-you-go basis. This made high-quality service feasible for small and medium-sized businesses for the first time.

The alteration in the IT market made by Amazon was fundamental. It was a “disruption” on the same scale that the 79 A.D. eruption of Mount Vesuvius was a “spillover.”

Prior to Amazon, software was intellectual property, which a license granted you the rights to have. What mattered was where it was installed, and convenience dictated that such installations be local. Software had almost always been architected as services, more or less using SOA principles, but its dissemination in a functional economy required it to be manufactured, like any other durable good. So the sales channel that constituted the circulatory system of this economy, was effectively a durable goods channel that depended on inventory, shipping, and transportation logistics.

After Amazon, software is active functionality, which a service contract grants you the rights to use. What matters now are the connections through which those functions are made useful, in a healthy and growing Internet. Convenience dictates that the point of access for software be centralized, but that the actual locations of these running functions be distributed, and their operations centrally orchestrated. This is the function of a distributed cloud platform, which completely and entirely replaces the old VAR-oriented software sales channel. Rather than being a manufacturing center, a cloud service provider (CSP) is the propagator of software.

Amazon did not invent this business model. Engineers and business visionaries did have this concept in mind as early as the 1960s. But the components were not present at that time to implement that vision. By the time they were, only the people inspired by the vision they had — including Jeff Bezos — were available to make it a reality.

LEARN MORE:

How AWS’ cloud business model works today

While AWS still hosts VM-based Web sites, its modern business model is centered around delivering functionality to individuals and organizations, using the Web as its transit medium. Here, we mean “the Web” in its technical sense: the servers that use HTTP and HTTPS protocols to transact, and to exchange data packets. Folks often talk about the Web as the place where ZDNet is published. But modern software communicates with its user through the Web.

That software is hosted in what we lackadaisically refer to as “the cloud.” The AWS cloud is the collection of all network-connected servers on which its service platform is hosted. You’ve already read more definitions of “cloud” than there are clouds (in the sky), but here, we’re talking about the operating system that reformulates multiple servers into a cohesive unit. For a group of computers anywhere in the world to be one cloud, the following things have to be made feasible:

- They must be able to utilize virtualization (the ability for software to perform like hardware) to pool together the computing capability of multiple processors and multiple storage devices, along with those components’ network connectivity, into single, contiguous units. In other words, they must collect their resources so they can be perceived as one big computer rather than several little ones.

- The workloads that run on these resource pools must not be rooted to any physical location. That is to say, their memory, databases, and processes — however they may be contained — must be completely portable throughout the cloud.

- The resource pools that run these workloads must be capable of being provisioned through a self-service portal. This way, any customer who needs to run a process on a server may provision the virtual infrastructure (the pooled resources for processing and other functions) needed to host and support that process, by ordering it through the Web.

- All services must be made available on a per-use basis, usually in intervals of time consumed in the actual functioning of the service, as opposed to a one-time or renewable license.

The US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) declared that any CSP to which the US Government would subscribe, must at a minimum provide these four capabilities.

If NIST had the opportunity to add a fifth component, given the vast amount of history that has taken place in the few short years of the public cloud’s prominence, it would probably be support. AWS may be a public cloud, but it is also a managed service. That means it’s administered to deliver particular service levels which are explicitly spelled out in the company’s service-level agreements (SLA).

Most importantly today, no CSP is forced to offer its services from some remote location. AWS is among those providers building methods to extend premium options for its services to new classes of facilities, including smaller data centers in more locations, as well as inside customers’ premises. AWS Outposts (with limited availability today to select customers) the installation of Amazon virtual infrastructure, in any facility capable of hosting between 1 and 96 racks, each supporting 42 standard sizing units (42 U) of servers of 1 or 2 U in height. This service is being marketed for enterprise customers that run more deterministic (time-constrained) workloads such as machine learning and network analytics, for whom the latencies that accrue with communicating back and forth with cloud data centers, become intolerable over time.

LEARN MORE:

What is AWS’ place in a multicloud environment?

There is one element of the software economy that has not changed since back when folks were fathoming the “threat potential” of Microsoft Windows: The dominant players have the luxury of channeling functionality through their portals, their devices, and their service agreements. AWS uses the concept of “democratization” selectively, typically using it to mean increasing availability to a service that usually has a higher barrier to entry. For example, an AWS white paper co-produced with Intel, entitled “Democratizing High-Performance Computing,” includes this statement:

Of course, each organization understands its own needs best, but translating those needs into real-world compute resources does not need to be a cumbersome process. Smaller organizations would rather have their expensive engineering or research talent focus on what they do best, instead of figuring out their infrastructure needs.

Recently, AWS began producing management services for multicloud computing options, where enterprises pick-and-choose services from multiple cloud providers (there aren’t all that many now anyway). But these services are management consoles that install AWS as their gateways, channeling even the use of Azure or Google Cloud services through AWS’ monitoring.

AWS CEO Andy Jassy (due to become CEO of corporate parent Amazon.com Inc. in Q3 2021) explained his company’s stance on engaging with multiple service providers quite cleverly, in a speech presented as advice to growing businesses, at AWS’ virtual re:Invent 2020 conference:

One of the enemies of speed is complexity. And you have to make sure that you don’t over-complexify what you’re doing. When companies decide to make transformations and big shifts, a huge plethora of companies descend on them, and providers descend on them, and tell them all the ways that you’ve gotta use their products. “You need to use us for this, even if you’re using these people for these three things, use us for these two,” this company says, “Use us for this.” They don’t deal with the complexity that you have to deal with, in managing all those different technologies and capabilities. The reality is, for companies that are making big transformations and shifts, it is much easier to be successful if you predominantly choose a partner, and you learn how to do it, and you get momentum, and you get success, and you get real results for the company. Then later on, if you want to layer on complexity and more providers, you should go for it. But it’s not a great way to start a reinvention, to have too much complexity up front.

LEARN MORE:

How do you get started with AWS?

It surprises some to learn that an AWS account is not an Amazon account with extra privileges. It’s a security account that centralizes the access you’re given to AWS services, and associates that access with a billable address. Not a shipping address, like a destination for goods ordered from Amazon.com, but rather a login like the one you may use for Windows.

There are ways you can use this AWS account to launch yourself into the AWS space without much, or quite likely without any, monetary investment. For the first year of each account, AWS sets aside 750 hours of free usage per month (also known as “the entire month”) of a Linux- or Windows-based t2.micro virtual machine instance, which is configured like a single-CPU PC with 1 GB of RAM. Using that instance as a virtual server, you’re free to set up an instance of an Amazon RDS relational database with up to 20 GB of storage, plus another 5 GB of standard S3 object storage. (You’ll see more about these basic services momentarily.)

Where can you learn how to use AWS?

AWS convenes its own online conference, sometimes live but always recorded, called AWSome Day, whose intent is to teach newcomers about how its services work. That conference may give you a shove in the general direction of what you think you might need to know. If you have a particular business goal in mind, and you’re looking for professional instruction, AWS typically sponsors instructional courses worldwide that are conducted in training centers with professional instructors, and streamed to registered students. For example:

- Migrating to AWS teaches the principles that organizations would need to know to develop a staged migration from its existing business applications and software, to their cloud-based counterparts.

- AWS Security Fundamentals introduces the best practices, methodologies, and protocols that AWS uses to secure its services, in order that organizations that may be following specific security regimens can incorporate those practices into their own methods.

- AWS Technical Essentials gives an IT professional within an organization a more thorough introduction to Amazon services, and the security practices around them, with the goal being to help that admin or IT manager build and deploy those services that are best suited to achieving business objectives.

These conferences are, in normal times, delivered live and in-person. AWS suspended this program in 2020 due to the pandemic, although listings are available for virtual sessions that were recorded before that time. How affordable is AWS really?

AWS’ business model was designed to shift expenses for business computing from capital expenditures to operational expenditures. Theoretically, a commodity whose costs are incurred monthly, or at least more gradually, is more sustainable.

But unlike a regular expense such as electricity or insurance, public cloud services tend to spawn more public cloud services. Although AWS clearly divides expenses into categories pertaining to storage, bandwidth usage, and compute cycle time, these categories are not the services themselves. Rather, they are the product of the services you choose, and by choosing more and incorporating more of these components into the cloud-based assets you build on the AWS platform, you “consume” these commodities at a more rapid rate.

AWS has a clear plan in mind: It draws you into an account with a tier of no-cost service with which you can comfortably experiment with building a Web server, or launching a database, prior to taking those services live. Ironically, it’s through this strategy of starting small and building gradually, that many organizations are discovering they hadn’t accounted for just how great an operational expense the public cloud could become — particularly with respect to data consumption.

The no-cost service is AWS’ free tier, where all of its principal services are made available at a level where individuals — especially developers — are able to learn how to use them without incurring charges.

Cost control is feasible, if you take the time to thoroughly train yourself on the proper and strategic use of the components of the AWS platform, before you begin provisioning services on that platform. And the resources for that cost control training do exist, even on the platform itself.

LEARN MORE:

AWS basic services

Back in the days when software was manufactured, stored in inventory, and placed on retailers’ shelves for display, the “platform” was the dependency that was pre-engineered into a product that made it dependent upon others, or made others dependent upon it. MS-DOS was the first truly successful commercial software platform, mostly because of the dependencies it created, and which Microsoft would later exploit more deeply with Windows.

Amazon’s services are not dependent upon one another. On AWS, the platform is the fact that you’re being channeled through it as your CSP. Certainly AWS offers third-party services through its AWS Marketplace. But this app store-like environment is presented more as a bazaar, adjacent to, though not directly connected to, the principal services Amazon produces and makes available through its cloud console.

Elastic Compute Cloud

The product name for the first automated service that AWS performs for customers is Amazon Elastic Compute Cloud (EC2). This is the place where AWS pools its virtual resources into instances of virtual machines, and stages those instances in locations chosen by the customer to best suit its applications.

Originally, the configurations of EC2 instances mimicked those of real-world, physical servers. You chose an instance that best suited the characteristics of the server that you’d normally have purchased, installed, and maintained on your own corporate premises, to run the application you intended for it. Today, an EC2 instance can be almost fanciful, configured like no server ever manufactured anywhere in the world. Since virtual servers comprise essentially the entire Web services industry now, it doesn’t matter that there’s no correspondence with reality. You peruse AWS’ very extensive catalog, and choose the number of processors, local storage, local memory, connectivity, and bandwidth that your applications require. And if that’s more than in any real server ever manufactured, so what?

You then pay for the resources that instance uses, literally on a per-second basis. If the application you’ve planned is very extensive, like a multi-player game, then you can reasonably estimate what your AWS costs would be for delivering that game to each player, and calculate a subscription fee you can charge that player that earns you a respectable profit.

LEARN MORE:

Elastic Container Service

Virtual machines gave organizations a way to deliver functionality through the Internet without having to change the way their applications were architected. They still “believe” they’re running in a manufactured server.

In recent years, a new vehicle for packaging functionality has come about that is far better suited to cloud-based delivery. It was called the “Docker container,” after the company that first developed an automated mechanism for deploying it on a cloud platform (even though its name at the time was dotCloud). Today, since so many parties have a vested interest in its success, and also because the English language has run out of words, this package is just called a container.

AWS’ way to deliver applications through containers rather than virtual machines is Elastic Container Service (ECS). Here, the business model can be completely different than for EC2.

Because a containerized application (sorry, there’s no other term for it) may use a variable amount of resources at any particular time, you may opt to pay only for the resources that application does use, at the time it requests them. As an analogy, think of it like this: Instead of renting a car, you lease the road, pay for the gasoline consumed with each engine revolution, the oxygen burned with each ignition of a cylinder, and the amount of carbon dioxide produced by the catalytic converter. With ECS, you’re renting the bandwidth and paying for the precise volume of data consumed and the cycles required for processing, for each second of your application’s operation. Amazon calls this pricing model Fargate, referring to the furthest possible point in the delivery chain where the “turnstile” is rotated and where charges may be incurred.

LEARN MORE:

Simple Cloud Storage Service (S3)

As we mentioned before, one of Amazon’s true breakthroughs was the establishment of S3, its Simple Storage Service (the word “Cloud” has since been wedged into the middle of its name). For this business model, Amazon places “turnstiles,” if you will, at two points of the data exchange process: when data is uploaded, and when it’s transacted by means of a retrieval call or a database query. So both input and output incur charges.

AWS does not charge customers by the storage volume, or in any fraction of a physical device consumed by data. Instead, it creates a virtual construct called a bucket, and assigns that to an account. Essentially, this bucket is bottomless; it provides database tools and other services with a means to address the data contained within it. By default, each account may operate up to 100 buckets, though that limit may be increased upon request.

Once data is stored in one of these buckets, the way AWS monetizes its output from the bucket depends upon how that data is used. If a small amount of data is stored and retrieved not very often, AWS is happy not to charge anything at all. But if you’ve already deployed a Web app that has multiple users, and in the course of using this app, these users all access data stored in an S3 bucket, that’s likely to incur some charges. Database queries, such as retrieving billing information or statistics, will be charged very differently from downloading a video or media file.

If AWS were to charge one flat fee for data retrieval — say, per megabyte downloaded — then with the huge difference in scale between a spreadsheet’s worth of tabular data and a 1080p video, no one would want to use AWS for media. So S3 assumes that the types of objects that you’ll store in buckets will determine the way those objects will be used (“consumed”) by others, and AWS establishes a fee for the method of use.

LEARN MORE:

AWS database services

Here’s where Amazon adds a third turnstile to the data model: by offering database engines capable of utilizing the data stored in S3 buckets. An AWS database engine is a specialized instance type: a VM image in which the database management system is already installed.

Amazon Aurora

For relational data — the kind that’s stored in tables and queried using SQL language — AWS offers a variety of options, including MariaDB (open source), Microsoft SQL Server, MySQL (open source), Oracle DB, PostgreSQL (open source). Any application that can interface with a database in one of these formats, even if it wasn’t written for the cloud to begin with, can be made to run with one of these services.

AWS’ own relational design is called Aurora. It’s a unique database architecture built around and for S3. As Amazon CTO Werner Vogels explained in a 2019 blog post, rather than construct database tables as pages and build logs around them to track their history, Aurora actually writes its database as a log. What appear to users to be page tables are actually reconstructions of the data, by way of the instructions stored in the logs, which are themselves stored redundantly.

Since data is always being reconstructed as a matter of course, any loss of data is almost instantaneously patched, without the need for a comprehensive recovery plan. In the case of severe loss, such as an entire volume or “protection group,” repairs are accomplished by way of instructions gleaned from all the other groups in the database, or what Vogels calls the “fleet.”

LEARN MORE:

Amazon Redshift

Standing up a “big data” system, such as one based on the Apache Hadoop or Apache Spark framework, is typically a concentrated effort on the part of any organization. Though they both refrain from invoking the phrase, both Spark and Hadoop are operating systems, enabling servers to support clusters of coordinated data providers as their core functionality. So any effort to leverage the cloud for a big data platform must involve configuring the applications running on these platforms to recognize the cloud as their storage center.

AWS Redshift approaches this issue by enabling S3 to serve as what Hadoop and Spark engineers call a data lake — a massive pool of not-necessarily-structured, unprocessed, unrefined data. Originally, data lakes were “formatted,” to borrow an old phrase, using Hadoop’s HDFS file system. Some engineers have since found S3 actually preferable to HDFS, and some go so far as to argue S3 is more cost-effective. Apache Hadoop now ships with its own S3 connector, enabling organizations that run Hadoop on-premises to leverage cloud-based S3 instead of their own on-premises storage.

In a big data framework, the operating system clusters together servers, with both their processing and local storage, as single units. So scaling out processor power means increasing storage; likewise, tending to the need for more space for data means adding CPUs. AWS’ approach to stationing the entire big data framework in the cloud is not to correlate Spark or Hadoop nodes as unaltered virtual machines, but instead deploy a somewhat different framework that manages Hadoop or Spark applications, but enable S3-based data lakes to become scalable independently. AWS calls this system EMR, and it’s made considerable inroads, capitalizing on Amazon’s success in substituting for HDFS.

LEARN MORE:

Amazon Kinesis Data Analytics

Kinesis leverages AWS’ data lake components to stand up an analytics service — one that evaluates the underlying patterns within a data stream or a time series, make respectable forecasts, and draw apparent correlations as close to real-time as possible. So if you have a data source such as a server log, machines on a manufacturing or assembly line, a financial trading system, or in the most extensive example, a video stream, Kinesis can be programmed to generate alerts and analytical messages in response to conditions that you specify.

The word “programmed” is meant rather intentionally here. Using components such as Kinesis Streams, you do write custom logic code to specify those conditions that are worthy of attention or examination. By contrast, Kinesis Data Firehose can be set up with easier-to-explain filters that can divert certain data from the main stream, based on conditions or parameters, into a location such as another S3 bucket for later analysis.

LEARN MORE:

In addition, AWS offers the following:

- DynamoDB for use with less structured key/value stores

- DocumentDB for working with long-form text data such as in a content management system

- Athena as a “serverless” service that enables independent queries on S3-based data stores using SQL

- ElastiCache for dealing with high volumes of data in-memory.

AWS advanced and scientific services

Amazon Lambda

One very important service that emerges from the system that makes ECS possible is called Lambda, and for many classes of industry and academia, it’s already significantly changing the way applications are being conceived. Lambda advances a principle called the serverless model, in which the cloud server delivers the functions that an application may require on a per-use basis only, without the need for pre-provisioning.

For instance, if you have a function that analyzes a photograph and isolates the portion of it that’s likely to contain the image of a human face, you can stage that function in Amazon’s cloud using the serverless model. You’re not being charged for the VM or the container hosting the function, or any of the resources it requires; rather, AWS places its “turnstile” at the point where the function renders its result and terminates. So you’re charged a flat fee for the transaction.

Although Amazon may not have had the idea for the serverless model, Lambda has advanced that model considerably. Now developers are reconsidering the very nature of application architecture, with the end result being that an entirely new economy may emerge around fluid components of functionality, as opposed to rigid, undecipherable monoliths.

LEARN MORE:

Amazon Elastic Container Service for Kubernetes

As Microsoft so often demonstrated during its reign as the king of the operating system, if you own the underlying platform, you can give away parts of the territory that floats on top of it, secure in the knowledge that you own the kingdom to which those islands belong.

In founding the market for virtualization, VMware set about to relocate the seat of power in the data center kingdom to the hypervisor. And in drawing most of the map for the public cloud market, Amazon tried to relocate it to the EC2 instance. Both efforts have yielded success. But Kubernetes, as an open source orchestrator of container-based applications, sought to plant a bomb beneath that seat of power, by effectively democratizing the way new classes of applications were created and deployed. It was Google’s idea, though with just the right dosage of benevolence, Docker would step aside, bowing graciously, and even Microsoft would contribute to the plan.

AWS’ managed Kubernetes service, called EKS and launched in July 2018, represents Amazon’s concession to the tides of history, at least for this round. The previous July, Amazon joined the Cloud Native Computing Foundation — the arm of the Linux Foundation that oversees development of the Kubernetes orchestrator.

This way, EKS can provide management services over the infrastructure supporting a customer’s Kubernetes deployment, comparable to what Google Cloud and Azure offer. The provisioning of clusters can happen automatically. That last sentence doesn’t have much meaning unless you’ve read tens of thousands of pages of Kubernetes documentation, the most important sentence from which is this: You can pick a containerized application, tell EKS to run it, then EKS will configure the resources that application requires, you sign off on them, and it runs the app.

So if you have, say, an open source content management system compiled to run in containers, you just point EKS to the repository where those containers are located and say “Go.” If all the world’s applications could be automated in exactly this way, we would be living in a very different world.

LEARN MORE: