Art and Ayodhya have come together here; a pattern that is part of a slow, ongoing and ambitious remaking of India’s cultural sector in the mould of Hindutva nationalism. Premier art institutions under government patronage are mirroring society and the national mood like American painter Norman Rockwell did in his war effort. As the BJP has consolidated political power in the past decade, the capture of art spaces has begun too—after book publishing, cinema and textbooks.

“In the days to come, we will be stronger in this sphere. Now we need to focus on building a pool of art critics who will work towards bringing truth and divinity together,” said RSS Sarsanghchalak Mohan Bhagwat in February this year.

The NGMA exhibition needed to mimic the scale and scope of the inauguration, and so, curator Jyoti Tokas pulled out all stops. The NGMA’s entire collection was mined, which includes representations of the epic by Jamini Roy, Nandalal Bose and Chittaprosad Bhattacharya—and even then it wasn’t enough. The National Museum, the Delhi Art Gallery—art in its many forms was procured from different corners to curate a fulsome experience of the Ramayana. A hologram made it in too, a visualisation of the Sunderkand, the fifth part of the Ramayana.

“We can’t comment on how long the Ramayana’s been a part of our culture,” says Tokas. She’s been the gallery’s deputy director and curator since 2016. “But it needs to be for everyone. So we included the hologram and the virtual reality experience. Everyone loved it,” she said.

The Lalit Kala Akademi and the National Gallery of Modern Art, the country’s premier government art institutes, built as corpora for and of the preservation of Indian art and artists, are witnessing tectonic shifts—in tandem with the rest of the country. The exhibitions now have clear-cut themes, set to promote the Prime Minister’s initiatives, with Viksit Bharat and Swachch Bharat taking centre stage. LKA also routinely collaborates with the Sanskar Bharti, the cultural wing of the RSS.

As the BJP has consolidated political power in the past decade, the capture of art spaces has begun too—after book publishing, cinema and textbooks.

“Our goals are the same. Both of us want to create an atmosphere that pushes Indian culture forward. We want to end this era of slavery,” says Prabhat Kumar, Sanskar Bharti Executive President, Delhi Prant. “Everything is good in India. The West’s hold over culture is ebbing.”

Unsubtle references to India’s cultural supremacy, as shaped by the government’s pet-phrases and policies are standard now. In March, LKA in collaboration with the NGMA held a ‘Viksit Bharat Ambassador Artist Workshop’. Open to all who signed up, with advertisements online and in newspapers, it took place in Delhi’s Purana Qila. Regional centres in Chennai and Bhubaneswar also held sessions.

The creations from the workshop can roughly be divided into two categories. First, patriotism fused with a tech and infra-heavy version of the future, sky-high buildings and rocket ships. Second, the simpler, safer option—Prime Minister Narendra Modi. But creativity isn’t amiss here either. There’s Modi with Ram looking demurely over his shoulder, and Modi in his dusanand avatar—his other heads are his ministers, including Amit Shah. Modi himself made an appearance at the workshop, handing out certificates containing a photograph of him.

Artist Rahul Soni, who was part of the workshop, posted a reel of his time at the event, the cover of which showed him with both Modis—real and picturised.

“If the Prime Minister and the intellectual people of our country are saying that India will be developed by 2047, why shouldn’t artists be part of it? Why should artists be left behind? Over 10,000 artists participated. No such camp had ever happened before,” says Goutam. “People told me to put it up for a world record, but the moment is more important to me,” he adds, modestly. The workshop was attended by young, relatively unknown artists—most of whom aren’t part of the art circuit. But some have large followings on Instagram.

If the Prime Minister and the intellectual people of our country are saying that India will be developed by 2047, why shouldn’t artists be part of it? Why should artists be left behind?

– Sanjiv Kishor Goutam, director general, NGMA

When it comes to Viksit Bharat, artists let their imagination melt into their belief. There was a sense among the artists that they were on the cusp of national greatness. “There’s no limitation on dreams. In 2047, young artists will remember—this is how we imagined it. And common people participated,” says Goutam.

Before the onset of Modi, the same event would have taken place in an air-conditioned room, and would’ve comprised solely of “intellectual people.” Previously, the workshops were smaller. They didn’t have specific themes and were conducted largely for the promotion of artists. The Viksit Bharat workshop marked a first.

Also read: Sahitya Akademi is promoting Ramayana, Modi policies. But also queer & Dalit writers now

A space for emerging artists

A couple of months ago, chairman V Nagdas was stripped of his responsibilities. There was a dispute between him and the secretary, and the Ministry of Culture needed to interfere, a senior official who did not want to be named said. Nagdas was supposedly stepping on the secretary’s toes. Lalit Kala Akademi is one of three autonomous institutes under the ministry.

Though the Akademi is currently operating without a chairman, exhibitions are ongoing.

On display now at the Lalit Kala gallery, located in the quiet Rabindra Bhawan, is art by Buddhi Thapa, a Naga painter. It’s an exploration of consciousness and was inaugurated by a psychologist.

The Akademi exists to enable work by Indian artists, and serve as a support system for them. The caveat, as specified by those in the industry, is that the Ministry of Culture cannot dictate the content of exhibitions or work done by individual artists. There was never any official cultural policy, but it was an unspoken principle.

But, according to a young artist—what is evident today is the makeup of the governing body. Apart from wanting to bring together artists to paint murals on scenes from the Ramayana, Chairman Nagdas also proposed an “on-the-spot painting competition” in Ayodhya and an exhibition of Ram’s human face. The younger artist’s politics are fundamentally different, but for emerging creators artists, the space is essential.

“It’s not expensive. Other galleries like Triveni and Bikaner House are selective and difficult to get into. LKA gives everyone a chance,” says the young artist on the condition of anonymity. His group show at LKA was completed within a budget of less than Rs. 70,000—which would have been unthinkable in another space.

But there’s a caveat—“You have to censor yourself.”

For instance, some of his work looks at ecological collapse, as aggravated by state-sponsored development. This, according to him, wouldn’t necessarily fly with the LKA jury. But the benefits are undeniable.

There were other constraints as well. The lighting was subpar, he wasn’t allowed to position his paintings as he wished. When he complained, he was told he’d have to submit an application to the management. “Only 25 per cent of any exhibition is about the work itself. The rest is in framing, curation and lighting,” he says.

There also isn’t much footfall—potential for buyers as well as overall numbers are far higher in Triveni and Bikaner House.

“It’s a difficult space. They don’t let you put nails on their walls. And you need to have additional expenditure. Presentation style has really changed. That flexibility is required,” says curator Gigi Scaria, who also presented at the Akademi as part of group shows. In the mid-1990s, Scaria participated in ‘The Gifts of India’, held to honour 50 years of Independence. In 2010, there was ‘Magical Realism’, curated by Sunil Mehra.

It’s not expensive. Other galleries like Triveni and Bikaner House are selective and difficult to get into. LKA gives everyone a chance, but you have to censor yourself

– young artist

However, LKA remains integral to the circuit. “So many interesting shows were done in the space. Though, now people aren’t approaching it as much. It’s an amazing space, located in the center of the city,” Scaria says. “When I moved to Delhi in 1995, it was our adda—a vibrant, intellecutal heart.”

He’d think twice before exhibiting there now, particularly because his most recent show Moments in Collapse, presented at Jawahar Bhawan, is subversive. There’s work that is unbashedly critical of the times we live in—regardless of the lens through which it’s viewed. Urgent Saaru by Pushpamala, is a live cooking performance of a curry that Gauri Lankesh used to make on the regular—V Pushpamala was the murdered journalist’s neighbour. Sanjay Sharma’s Drainage shows shredded newspapers, as contents of a sewer. Pablo Bartholomew’s photographs on the demolition Babri Masjid are on display, stark reminders of the violence that culminated in destruction. A portion of the floor is covered with lotus-shaped candles. Attendees are given the option to melt them.

For the Sanskar Bharti, on the other hand, the LKA emerged as a haven of sorts. In both 2022 and 2023, their Dilli Kala Mahotsav was held in Rabindra Bhawan. In 2022, the exhibition was based on Bhartiya Sanskriti, and in 2023, held just a month before the temple inauguration—the space was filled with about a hundred interpretations of Samvatsara ke Nayak Ram (Year of Ram), all by Sanskar Bharti’s artists. There are several dozens of Sanskar Bharti artists in Delhi alone; driven by the same ethos: Bhartiya Drishti (Indian vision).

But, the organisation doesn’t operate in any official capacity, and exists merely to spread a message.

“Sanskar Bharti is an NGO, we have nothing to do with the government,” says Kumar, adding, “We’re not dependent on them [LKA]. But it’s a mutual relationship. Sometimes they come to us, other times we go to them.” A copper idol of RSS founder Keshav Baliram Hedgewar sits perched on his desk.

In 2015, a year after the Modi government came to power, Cultural Continuity—from Rigveda to Robotics, was inaugurated at the LKA, by known RSS ideologues. Conceptualised by a Hyderabad non-profit, Institute of Scientific Research on Vedas (I-SERVE), which seeks to ‘scientifically’ prove that events in Indian epics took place in the real world. The exhibition had charts of data on the position of stars during significant events described in the epics, as well as the birthdate of Ram and the date of his exile, ostensibly proven through detailed calculations.

Also read: India’s cultural renaissance has begun. IGNCA leading it with Vastu, Vedas, and ‘new’ history

A nationalistic agenda

Much like the other institutions of its ilk, Lalit Kala Akademi, both its Delhi chapter and regional centres were heavily involved in celebrating Azadi ka Amrit Mahotsav. It’s appreciating the dawn of the new era, and creative practitioners are supposed to be ahead of the curve. And anyway, marching to the beat of a government drum isn’t a new phenomenon.

“The government always lays down certain policies. Earlier, they used to take things from the West and project them as being of utmost importance,” Bharat Gupt, NGMA trustee and former Delhi University professor practically scoffs, giving the example of Marxist theory and philosophy.

According to the Lalit Kala Akademi website, between January and February of last year, at least six events were held to commemorate Azadi Ka Amrit Mahotsav. A number of disparate events were clubbed under the same umbrella—photography walks, a “mela moments” competition, a portrait and beauty lighting workshop, and a miniature painting camp. There were no prescribed themes but Swachch Bharat featured prominently.

The government always lays down certain policies. Earlier, they used to take things from the West and project them as being of utmost importance

-Bharat Gupt, NGMA trustee

NGMA took contemporary cultural nationalism a step further, and the Ministry of Culture inducted the Indian art world’s biggest names. With Kiran Nadar as advisor, Jana Shakti, an homage to Narendra Modi’s Mann ki Baat, took place at NGMA. On display last May, 13 artists furnished its ‘themes’—the Covid crisis, health and fitness, India’s technological prowess, to name a few—by offering up sculptures, paintings, and installations. The Prime Minister’s Museum also has recordings of hundreds of Mann ki Baat episodes.

“This exhibition attempts to translate the creative processes of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s program Mann Ki Baat —both in terms of the idea as well as content — into works of art through artistic interpretation,” read the catalogue.

It was curated by art historian Alka Pande, and comprised work by various artists who had previously been vocal in their criticism of the government’s ideological identity. Now, they were “responding” to episodes from Mann ki Baat. This included Riyas Komu, one of the founders of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, whose work borrows from social and political movements. He told The Indian Express he was using Swachch Bharat to talk about the “plight of manual scavengers.”

Atul Dodiya’s fantastical interpretation of the Covid-19 crisis consisted of a mother shielding her child. It mirrored his understanding of India protecting her population during the pandemic. Paresh Maity presented what was called ‘Tan ki Man’. It appears to depict body-mind synchronicity, and there are multiple photographs from various angles of Maity and Modi studying the work together.

This is a far cry from 2015, when 39 writers returned their Sahitya Akademi awards in protest against the organisations’s silence in the face of increasing governmental intolerance. Termed ‘award-wapsi,’ former LKA chairman and culture secretary Ashok Vajpeyi was one of the first to do so. A decade later, a number of artists seem to have been co-opted by the government; their work utlised to enhance government narratives.

“The artists, many of whom have been working on Gandhi, Ambedkar, Buddha, environment, farmers‘ rights, women’s empowerment, and so on, will lose credibility, as these are exactly what this government has been working against. But they may get lucrative government patronage and commissions,” wrote visual artist Pushpamala N in the India Cultural Forum when the exhibit was on display.

A decade after award-wapsi, a number of artists seem to have been co-opted by the government; their work utlised to enhance government narratives.

Pande was approached not by the Ministry of Culture, but by arguably India’s most well-known art collector, Kiran Nadar.

“Art is all about trends. And cultural nationalism is taking place across institutions. Primary funding comes from the government, so there’s definitely been a shift—especially in the kinds of shows that are being done by the NGMA,” Pande told ThePrint, declining to comment on Jana Shakti. “There’s far more of a nationalistic agenda now.”

While private museums and collectors are looking outward, attuned towards global concepts and movements, government institutions are located firmly inside the country; unwilling to take a single step outside.

Mumbai’s Method is exploring gender dysmorphia and childhood trauma. Nature Morte just finished a show by London-based artist and photographer Lorenzo Vitturi, whose is art situated in his origins—Peru and Italy.

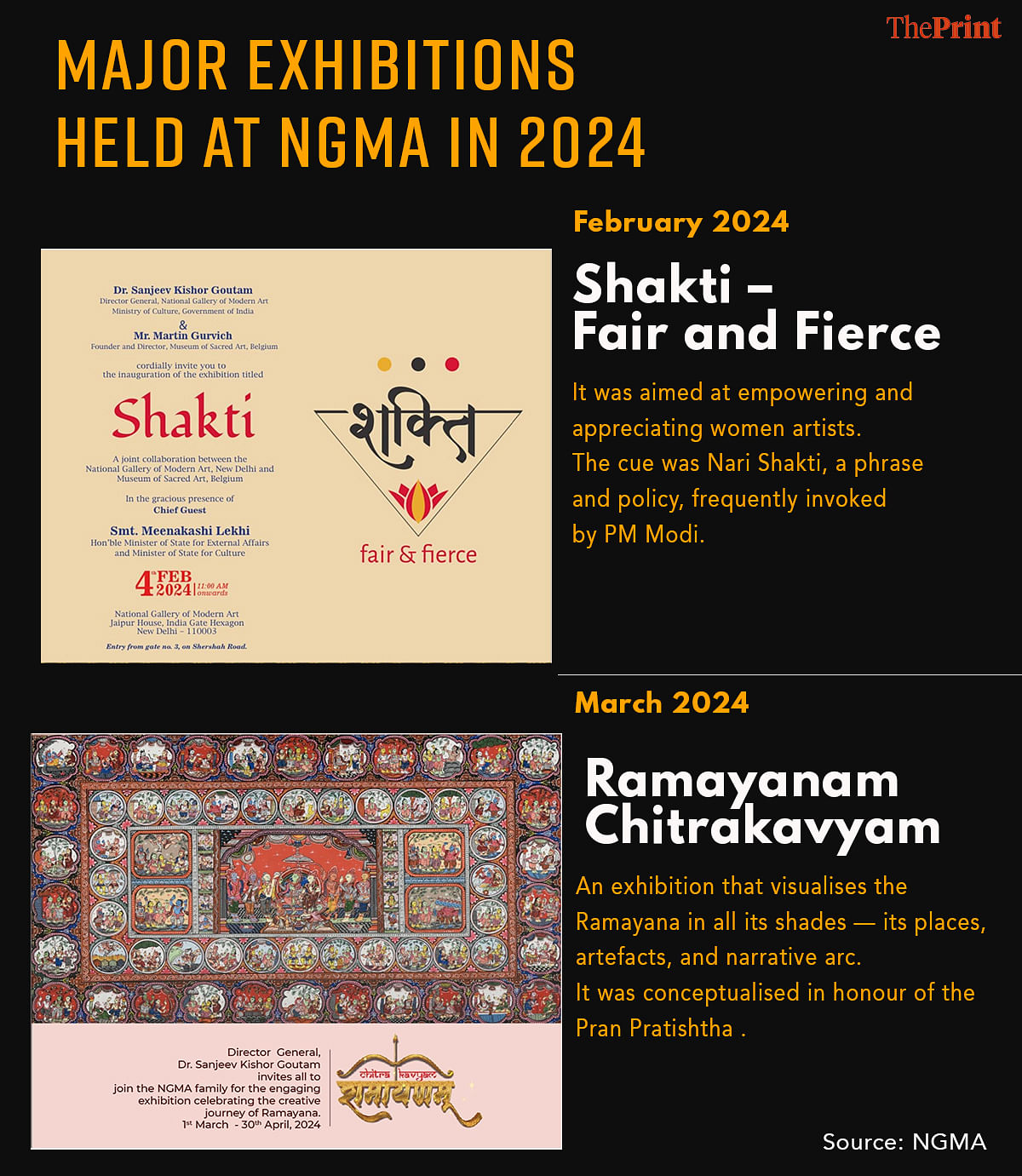

Goutam’s tenure in NGMA began in December 2023. Other than Ramayanam Chitrakavyam, which is now moving to NGMA Mumbai, his major order of business has been Shakti—Fair and Fierce, organised in collaboration with the Museum of Sacred Heart, a Belgium-based art gallery. Work from women artists across the country, many of whom were “unknown and from tribal communities”, was shown. It opened on Women’s Day, and was simultaneously showcased in Belgium.

“NGMA is not just a museum. We have to be responsible for citizens. We need to do work that attracts people to us,” says Goutam, going on to explain that if the Prime Minister is talking about Nari Shakti, so should everyone else. But even if it wasn’t for him—it’s a conversation that must be had, he adds earnestly. “It’s a good message to the country. The government doesn’t do anything for itself, it’s all for the people. That’s what NGMA does as well.”

Art is all about trends. And cultural nationalism is taking place across institutions. Primary funding comes from the government, so there’s definitely been a shift—especially in the kinds of shows that are being done by the NGMA

– Alka Pande, art historian, curator

Also read: ‘India’s only nationalist historian’ — ASI’s go-to curator was a card-carrying communist

From international art to regional artists

From 1993 to 2000, Anjali Sen held the reins at NGMA. The economy had just been liberalised, and geographical barriers were no longer sacrosanct—Indian art could be a cultural export and an import. Sen wanted to make NGMA international. Back then, she says, this many Indians weren’t travelling abroad. NGMA was one of the few outlets to experience global art.

“It was an extremely different context. We weren’t exposed to what was happening globally. I wanted to make sure NGMA wasn’t seen as elite or as a closed-door space,” she says.

She brought in a show by American photographer Cindy Sherman, originally put up at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Sherman’s work deals with identity and fragmentary notions of the self. NGMA also housed an exhibition on contemporary French art, for which Sen worked closely with the French Embassy. Today, the gallery works closely with the ICCR (Indian Council of Cultural Relations) to send its exhibitions abroad. Last year, an exhibit on India’s national treasures was shown in three museums across Japan. Amrita Sher-Gil’s paintings made it to South Africa for the first time. In the run-up to the G20 summit, the ministry built the G20 Digital Museum: Culture Corridor, for which NGMA was brought in. “All our energy went towards realising the summit’s goals,” says Meghna Arora, International Cultural Relations and Coordination in-charge.

About a five-minute drive away from NGMA, Lalit Kala Akademi’s internal churn also has roots in its past. In 2012, painter and sculptor Balan Nambiar, one of India’s leading contemporary artists was acting chairman. In a letter to the Minister of Culture, sent after his tenure was over, also in 2012, Nambiar lambasted the secretary and hurdles that, according to him, were stifling the Akademi.

“I tried to bring back the LKA to its past glory [when it had more reputed artists and the Triennale used to take place] by introducing various new schemes, many of which were introduced for the first time in the history of the Akademi. But all my efforts were thwarted by a single official who, at every stage, blocked my way by employing the most unethical methods,” wrote Nambiar in the letter, a copy of which was accessed by ThePrint. These consisted of favouritism when it came to gallery rentals, unfilled positions, and the “mismanagement” of scholarship funds.

“I could have brought the LKA to the notice of the art world globally if I had been given a few basic clearances,” Nambiar continued.

He also mentioned the Triennale, a flagship programme of the LKA, which hadn’t been held since 2006. The Triennale brought together an otherwise motley crew of artists, and gave them an essential platform. It used to be what the Akademi was known for.

Today, the gallery works closely with the ICCR to send its exhibitions abroad. Last year, an exhibit on India’s national treasures was shown in three museums across Japan. Amrita Sher-Gil’s paintings made it to South Africa for the first time.

There were grand plans for a revival in 2019, but soon after, according to an official, its funds were diverted—first for the Covid-19 pandemic, and then for the Azadi ka Amrit Mahotsav programmes. Now, the LKA prefers to focus on its other enterprises. “We have our mela mandir, and we’re focusing more on photography. Every young person has a phone, and they want to express their creativity. We want to give them a platform,” said the official. They’re currently working to beautify Yashobhoomi Convention Centre, located in Dwarka. The centre is a Bharat Mandapam equivalent, designed by the firm that redesigned Pragati Maidan and also created the masterplan of the Ayodhya township—CP Kukreja. NGMA, LKA, and IGNCA have been brought in to provide paintings and various cultural artefacts to be placed in and around the centre.

It’s bigger than a single institute. All of it is ultimately to usher in Viksit Bharat, to prepare for a developed India. “Every sector is looking for development. Progress is important in the art sector as well,” NGMA’s Goutam declares.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)