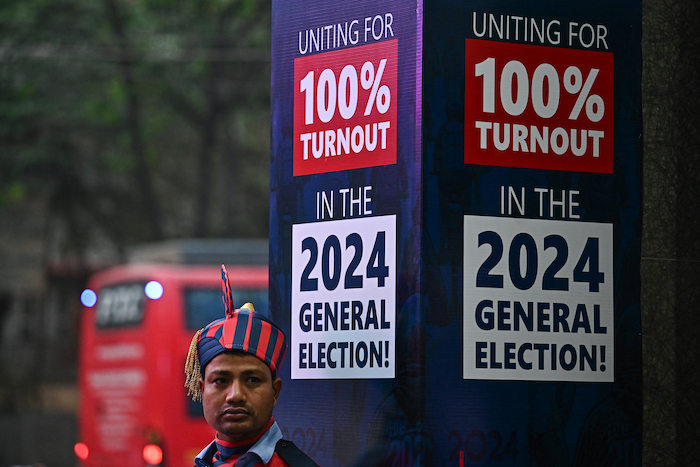

Almost one billion people will cast their votes between April 19 and June 1 in India’s momentous seven-phase national elections, which are widely expected to return Prime Minister Narendra Modi to an unprecedented third consecutive term. These elections are taking place against the backdrop of the country’s rapidly rising influence in world politics, especially after its successful G20 Presidency in 2023 – an event seen as signalling that “India’s moment has arrived.”

India’s 2024 elections are also an opportunity for Canadians to take stock of India’s economic and geopolitical rise and the world’s evolving relationship with this South Asian heavyweight. To that end, on March 18, the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada (APF Canada) convened a panel of experts to discuss the possible foreign policy implications of the elections and what India’s longer-term geopolitical ascendance might mean for Canada and the world’s major powers.

The panellists included Michael Kugelman, Director of the South Asia Institute at the Wilson Center in Washington, D.C.; Reeta Tremblay, Professor Emerita of Comparative Politics at the University of Victoria; and T.V. Paul, James McGill Professor of International Relations at McGill University, and Vina Nadjibulla, VP of Research & Strategy, APF Canada (Moderator). A summary of their discussion can be found below, and a video recording of the full conversation will be available soon on APF Canada’s website.

Major power, rising power, or middle power?

India’s remarkable rise is not without contradictions. For example, it is on track to become the world’s third-largest economy by 2030, but still scores low on many human development indicators. Despite these challenges, Prime Minister Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) remain popular. Michael Kugelman described Modi as a kind of ‘Teflon man’ who has managed to bounce back from several domestic political challenges during his tenure – the 2020-21 farmers’ protests, a surge in COVID-19 infections during the pandemic, and a sudden and controversial decision to demonetize the country’s currency in 2016.

One reason for Modi’s popularity, Kugelman explained, is Modi’s foreign policy successes. First, New Delhi has elevated its role on the world stage and has deepened engagement and strengthened relations with the regions it views as vital to its core interests: the Indo-Pacific, the Middle East, and the West. Second, India has scored some major strategic successes with its core foreign policy principle of strategic autonomy – avoiding alliances and joining formal ‘camps’ to maximize its strategic space and give itself ample foreign policy flexibility and independence. Its positioning on the world’s two most serious conflicts, Gaza and Ukraine, is a case in point. In the former, India has grown much closer to Israel while maintaining strong camaraderie with Arab states and solidarity with the Palestinians. In the case of the latter, India has preserved its “special and close relationship” with Russia while maintaining, if not strengthening, its relations with major Western powers.

And finally, reputationally, most of the world’s governments view India as a key strategic player and vitally important market. This helps explain why so many of these governments refrain from criticizing India too strongly for its perceived slide into illiberalism.

Pivoting to the domestic context, Reeta Tremblay highlighted that the Modi campaign has a powerful political narrative with three main messages. One is that the upcoming election will be a pro-incumbency vote and referendum on the past 10 years of Modi and the BJP’s accomplishments, including the promise of creating a developed India (“Viksit Bharat”) in the next 25 years. The second is the project of building India’s global brand as a leading power, responsible power, collaborative power, and leader of the Global South.

Third, to deepen its dominance at home, the Modi campaign has directed its attention to three key constituencies: the “backward”-caste Muslims, who make up 85 per cent of India’s Muslim population; the southern states, where the BJP’s political representation has been weaker than in the north; and in Sikh-majority Punjab, where the regional party Akali Dal – one of the BJP’s oldest allies – walked out of the alliance in 2020 during the farmers’ protests.

Whether these efforts pay off remains to be seen. A third term for Modi would consolidate the BJP’s nation-building and state-building projects, and promote the idea of India as a ‘civilizational power.’ However, the state of its liberal democracy will remain precarious.

In commenting on India’s rise, T.V. Paul argued that India is the second-most successful rising power after China. In the current “multiplex world order,” he said, India has gained first and foremost in terms of hard power, in the form of economic growth, military prowess, and technological advancements, but also in soft power, from its civilizational attributes, democratic institutions, and strong diaspora ties.

But in weighing whether India is a rising power or a major power, Professor Paul, paraphrasing from his forthcoming book, The Unfinished Quest: India’s Search for Major Power Status from Nehru to Modi, offered that status is like beauty, it lies in the eyes of the beholder. In other words, in its quest for greater geopolitical status, India will need external legitimization of that status.

Paul also argued that the international dimension of the forthcoming elections will be pivotal. Its relationship with the U.S. might become more transactional, especially if there is a second Trump Administration. And on Russia, he suggested, part of New Delhi’s calculation is not merely preserving a longstanding friendship but also not drawing Moscow closer to Beijing.

Perhaps the biggest challenge for India externally will be what it would do in the event of an armed conflict between China and Taiwan, or if the war in Ukraine escalates. These will be major tests for New Delhi. Would it be able to continue to adhere to strategic autonomy and a policy of ‘multi-alignment’?

Evolving strategic partnership with the West

APF Canada’s Vina Nadjibulla noted that a combination of economic and strategic factors has converged to bring the U.S. and other Western powers closer to India, helping to make it a more consequential player. As a reflection of this convergence, six World Trade Organization disputes between the U.S. and India were mutually resolved in 2023. And, as Michael Kugelman also pointed out, Pakistan – a longstanding U.S. ally and India’s main adversary – is no longer a point of tension between Washington and New Delhi. Even with the recent indictment in a New York court on a “murder-for-hire” plot allegedly involving an Indian official, the two countries’ strategic convergence around concerns about China is likely to prevent the relationship from unravelling.

Furthermore, India’s imports of U.S. military hardware have grown significantly in recent years as it seeks to reduce its dependence on Russia, especially as the latter draws closer to China. Moreover, trade relations and India’s overall economic weight will also be crucial. In 2023, the U.S. surpassed China to become India’s largest trading partner. Modi’s grand welcome in his maiden state visit to the U.S. in 2023 reflects how crucial the strategic partnership has become for both countries.

Regional competition and bid for leadership of the Global South

Except for Pakistan, India has historically enjoyed a hegemonic influence among smaller states in its neighbourhood. However, India’s geopolitical rise has coincided with a decline in this influence, especially vis-à-vis China. For example, its relationship with Maldives has recently hit a low, and even in countries like Nepal, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka, China has managed to chip away at India’s influence. The former’s Belt and Road Initiative and infrastructure development activities are a major factor in making it a much more prominent actor in the sub-region.

But, noted T.V. Paul, while New Delhi is trying to reckon with having to ‘share’ its leadership status in South Asia with China, it also seems to have concluded that South Asia is not the region that is going to make it a great power. Rather, it is looking to strengthen ties with countries further afield. On that task, Mr. Modi has been successful.

Challenges facing Indian foreign and domestic policies

Many Western stakeholders remain concerned about what they see as a decline in rights and freedoms in India. Meanwhile, India, which regards itself as a civilizational power, has articulated the idea of ‘cultural re-balancing,’ whereby a Western worldview should not set normative expectations for others. This will remain an enduring challenge in India’s relations with Western liberal democracies. For instance, New Delhi refuted the U.S. State Department’s concerns, on the grounds of religious freedoms, over its implementation of a contentious citizenship law as “misplaced, misinformed, and unwarranted.”

Professor Tremblay pointed to the BJP’s outreach to segments of the Muslim and Sikh communities in India – both religious minorities that have not been part of the BJP’s traditional support base – and noted that many Muslims remain wary of the 2019 citizenship law and threats to their religious freedoms. According to T.V. Paul, fears of rising illiberalism may undermine India’s ‘soft power,’ a vital component of its quest for great power status. Notwithstanding these challenges, he also noted that India’s expanding international presence and massive population should prompt a greater space for the country in global governance structures.

Paul added that India has been less successful in demonstrating leadership in global forums and on global issues such as climate action, tending to behave like a “veto power” or a naysayer, shooting down proposals but not providing solutions.

Canada remains an ‘outlier’

While U.S.-India relations have grown stronger, the same cannot be said of Canada. The diplomatic fallout of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s statement in September 2023 regarding India’s alleged involvement in the murder of a Canadian citizen on Canadian soil, and New Delhi’s much harsher response to those allegations in comparison to similar allegations in the U.S., have raised difficult questions about how Ottawa should engage with this key player in the Indo-Pacific.

Tremblay pointed out that in the 75 years of bilateral ties between India and Canada, almost a third of it – including the present – has been marred by tensions. The first big rupture happened in 1974 after India’s first nuclear tests using plutonium manufactured in a research reactor given to India by Canada. She added that even in the current moment, trade and investment ties have remained largely unaffected and exchanges at the subnational level have continued.

The challenges for Canada-India relations, she said, will centre around two questions: how Canada manages India’s expectations on the Khalistan issue without sacrificing its values and how Canada manages diaspora politics. Her remarks suggested that while Ottawa needs a more effective public relations and communications strategy to manage differences with India in the short term, in the longer term, both sides need to make serious strides in trust-building and removing historical and ideological roadblocks.

T.V. Paul commented on the ideological dissonance between the two countries, especially in how they frame their national interests. The Canadian approach is driven by a liberal worldview, which protects the right to self-determination and freedom of speech. In contrast, Indian strategic thinking considers the denigration of sovereignty and territorial integrity to be a serious national security threat. Thus, aspects of diaspora politics in Canada have become a serious bone of contention in the bilateral relationship.

What’s next?

Regardless of differences in perception, India’s geopolitical rise in the current era is a significant event and one that increasingly cements its relationship with the U.S. and other Western powers. Despite its reluctance to join formal alliances, New Delhi’s strategic partnership with the U.S. remains robust, especially as their interests and values align in promoting a peaceful, free, and open Indo-Pacific region.

The lingering question, as noted above, is what role India would play if rifts between major powers like the U.S. and China widen. Could New Delhi afford to antagonize China, given that it has a trade imbalance of almost US$100 billion in Beijing’s favour, or that the two sides’ border conflicts remain unresolved?

India will continue to be cautious in not abandoning its strategic autonomy or the enduring friendship it has had with Russia. If the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East intensify, will India be able to remain ‘multi-aligned’? And will Canada and India find a way to look past their differences to re-build closer relations?