For someone who lost a season to a nagging elbow injury that needed surgery, Indian javelin thrower Neeraj Chopra understandably welcomed the postponement of the Tokyo Games last year.

The mop-haired former world junior champion, potentially independent India’s first track-and-field Olympic medallist, had hoped to use the extra time to get back to full fitness and try to find his best form.

Instead, the 23-year-old was soon sent scurrying back indoors as the COVID-19 pandemic swept the world’s second-most populous nation, then surged again in a devastating second wave this year.

Chopra is one of 90-odd Tokyo-bound Indian athletes who have spent much of the last 12 months agonising over the loss of precious practice time in an Olympic year.

“There’s been an extended period of over two years since I competed in an international competition,” the javelin thrower recently told Reuters.

“As an athlete, there’s only so much one can train and the lack of competition is definitely a factor that’s been playing on my mind.”

India leads the world in the daily average number of new deaths reported, accounting for one in every three deaths reported worldwide each day, according to a Reuters tally.

Chopra was hoping to train and compete in Turkey this month but the Athletics Federation of India suspended their camp after being told the athletes would have to complete two weeks of hard quarantine on arrival.

The frustration for aspirant Olympians has been palpable and athletes like table tennis player Sathiyan Gnanasekaran have been forced to innovate to stay sharp during the lengthy lockdowns.

Left with no practice partner last year, the tech-savvy paddler used a ping pong robot he had imported from Germany and finally booked his Tokyo spot in March.

“It can fire around 120 balls per minute. It’s basically like a feeder one but you can add a lot of randomness into it,” the 28-year-old told Reuters by telephone.

“You can set up the ball trajectory and frequency, you can set up the spin and speed, you can set up like one ball close to the net, and then the other one at the far end of the table.

“So this is very close to what we practise with a coach or with a fellow player.”

Sathiyan has since turned the roof terrace of his Chennai home into a sports hall, ordered a new table just like the ones he will play on in Tokyo, and roped in a local player to practise against.

“Definitely robots can’t be compared to humans. I prefer sparring with humans any day,” he said.

“You miss that human touch. You miss those moments, like seeing openings and placing them in the right place.”

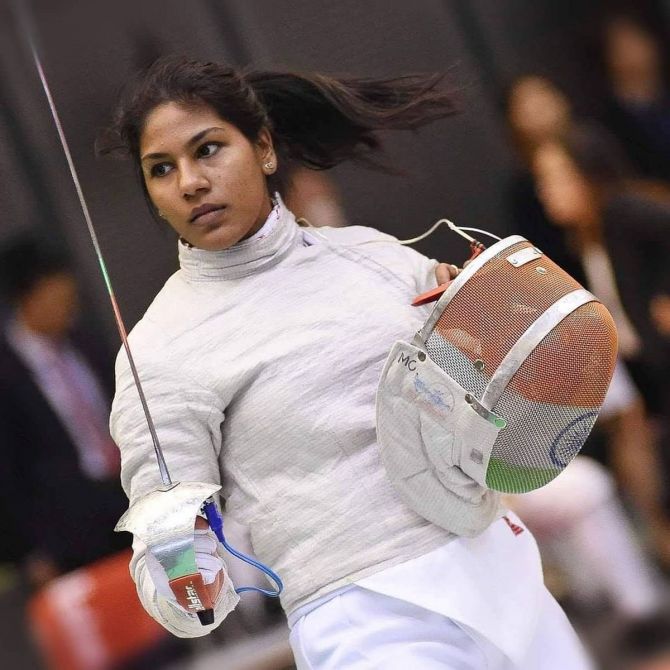

Elsewhere in Chennai, fencer Bhavani Devi faced the same challenge last year when her qualification hopes appeared hanging by a thread in the absence of a sparring partner.

The 27-year-old came up with a concrete plan — literally — piling bricks and slabs together under a kitbag with a fencing mask attached to it to create a dummy partner.

“It was not a new idea for me,” the sabre fencer told a virtual news conference on Wednesday, recalling the early days of her fencing career when she could not afford a proper sword and practised with bamboo sticks.

“I used to mount my mask on the wall and do my partner-training those days. It came from that.

“It gave me the feel of fencing with an opponent,” said Devi, who earlier this year became the first Indian fencer to qualify for an Olympics, booking her spot at the World Cup in Hungary.

Boxer Vikas Krishan roped in his family to help, teaching his father to hold the punching bag at his Bhiwani home.

“Having competed at two Olympics, I know what it takes to succeed at the highest level and I am not allowing anything to come in my way,” the 29-year-old welterweight told Reuters.

“My only aim for Tokyo is to win gold for India and I have focused all my efforts and energy to achieving that target.”