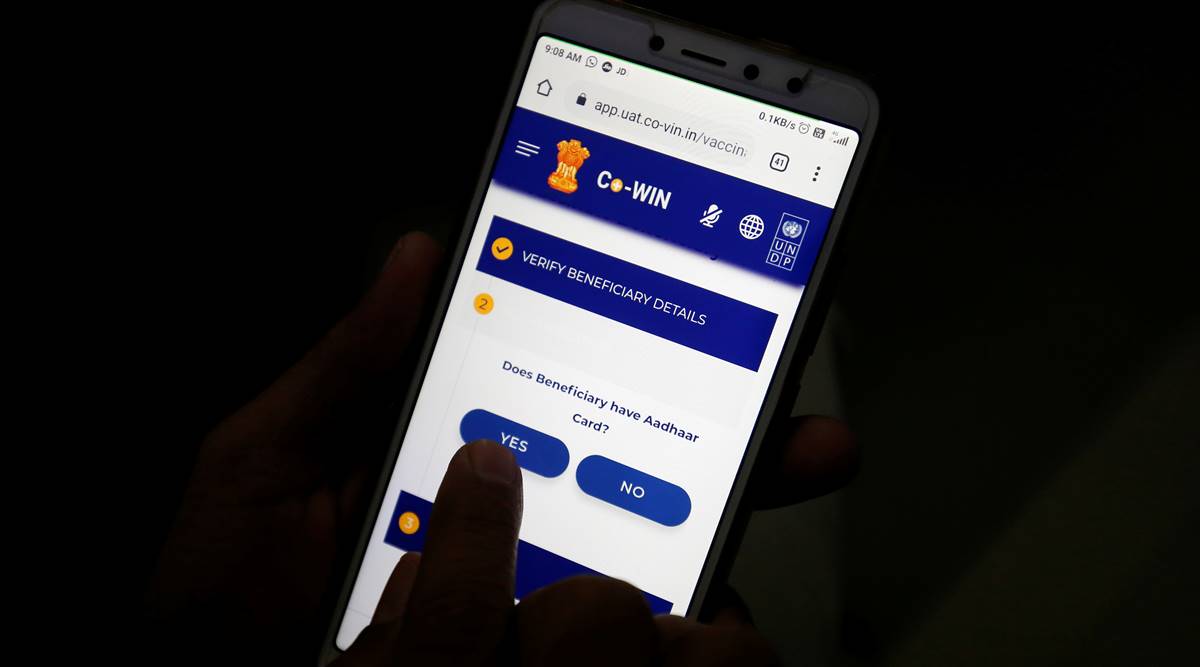

India is currently in the throes of a catastrophic second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic, which has exposed the severe lack of our health infrastructure. Since March 2021, we have seen the situation spiral out of control to the extent that people are now left with no choice but to crowdsource life-saving drugs, oxygen cylinders and hospital beds on the internet. Technology is serving us during this crisis and it is natural for it to be viewed as a measure for vaccination. Here, the principal response has been through the CoWin portal that has been launched by the Government of India to digitise the vaccination drive. It is, however, resulting in vaccine exclusion and a lack of privacy.

The most obvious criticism of the portal is its mandatory nature for vaccination in the 18-44 age group. CoWin, which on May 1 opened for registration of individuals ranging from 18-44 years of age, has come under criticism for its propensity to exclude people who are still on the other side of the digital divide as well as for its inherent design issues. According to the Indian Telecom Services Performance Indicator Report for October-December, 2020, released on April 27, 2021, the percentage of the rural population that subscribes to the internet is 34.60 per cent. It even conflicts with the early-stage learnings from CoWin’s own dashboard. On April 28, the dashboard showed that for the 45-plus age group, out of a total 14,42,10,652 vaccination registrations, only 2,52,96,511 were through CoWin.

In the absence of the internet and without knowledge of how the portal functions, the majority of India’s rural population is being discriminated against and a form of technical rationing is being implemented by CoWin based on broadband connectivity and digital literacy. This is anecdotally reinforced even in high connectivity areas. A report in this paper (IE, May 12) carries a self-explanatory headline, “In Delhi’s slums, barriers to vaccination: Few smartphones, English-only website”.

The second area of concern is that of data protection and cyber security. At present, vaccination slots on the portal are being released without any notice or schedule, and are being snatched up within seconds of being released by whoever is lucky enough to be checking the portal at the time, turning the vaccination drive into a game of “fastest finger first”. Even this metaphor is inaccurate as either through its official API or automated scripts, a range of functionality is available for people to automate functions ranging from notification to even slot reservation. These exist in multiple variations and risk exposure of medical healthcare data through third-party providers. It would be appropriate for the National Health Authority to issue an advisory or change the technical flow of CoWin to prevent such automation, which compounds exclusion and also risks the privacy of Indians.

However, CoWin’s own record speaks poorly on privacy. The CoWin website has no privacy policy even while India lacks a data protection law. While the Union Minister of State for Health, Ashwini Choubey, has provided, in a response to Parliament, an undertaking that the Data Privacy Policy of the National Health Mission would cover CoWin, on a finer reading of the policy, its applicability is not specifically defined. This is contrary to the Supreme Court’s right to privacy judgment but also to the departmental guidelines of the Government of India for official websites. The departmental guidelines clearly state that government websites when collecting personal data, “must incorporate a prominently displayed privacy statement…”.

In an interview on April 6, 2021, R S Sharma, the current CEO of the National Health Authority, revealed a pilot study stating that “Aadhaar-based facial recognition system could soon replace biometric fingerprint or iris scan machines at Covid-19 vaccination centres across the country in order to avoid infections.” Following criticism from public health and digital rights organisations, Sharma claimed that, “the process involves face authentication and not facial recognition”. This change in nomenclature means little. Facial recognition bundles within it the process of authentication and can match against a person’s own biometrics (as has been claimed) for identity authentication, or against the general population, which is a wider body of data, for surveillance and security. While the privacy risk in the latter is more significant, the former continues to erode rights.

Use of Aadhaar-based facial authentication for access to vaccines creates further technical barriers for universalisation of vaccination with a worrying prospect of false negative results. The available technical studies consistently demonstrate high error rates in facial authentication. Environmental factors as opposed to ideal laboratory conditions will further contribute to operational complexity. The technology is not mature enough for deployment and a pandemic is an inappropriate time for experimentation. Again, facial authentication is being piloted in a legal vacuum of a data protection law, where the facial recognition data that will be layered with medical healthcare data can be stored, captured and shared without any legal limits or practical safeguards.

The technocratic approach in using digital systems has prioritised data collection and efficiency over vaccine equity. It disregards the experience of public healthcare and digital rights experts. The present deployment of CoWin, rather than augmenting the right to health, is undermining it.

Gupta is executive director and Jain is policy counsel, Internet Freedom Foundation