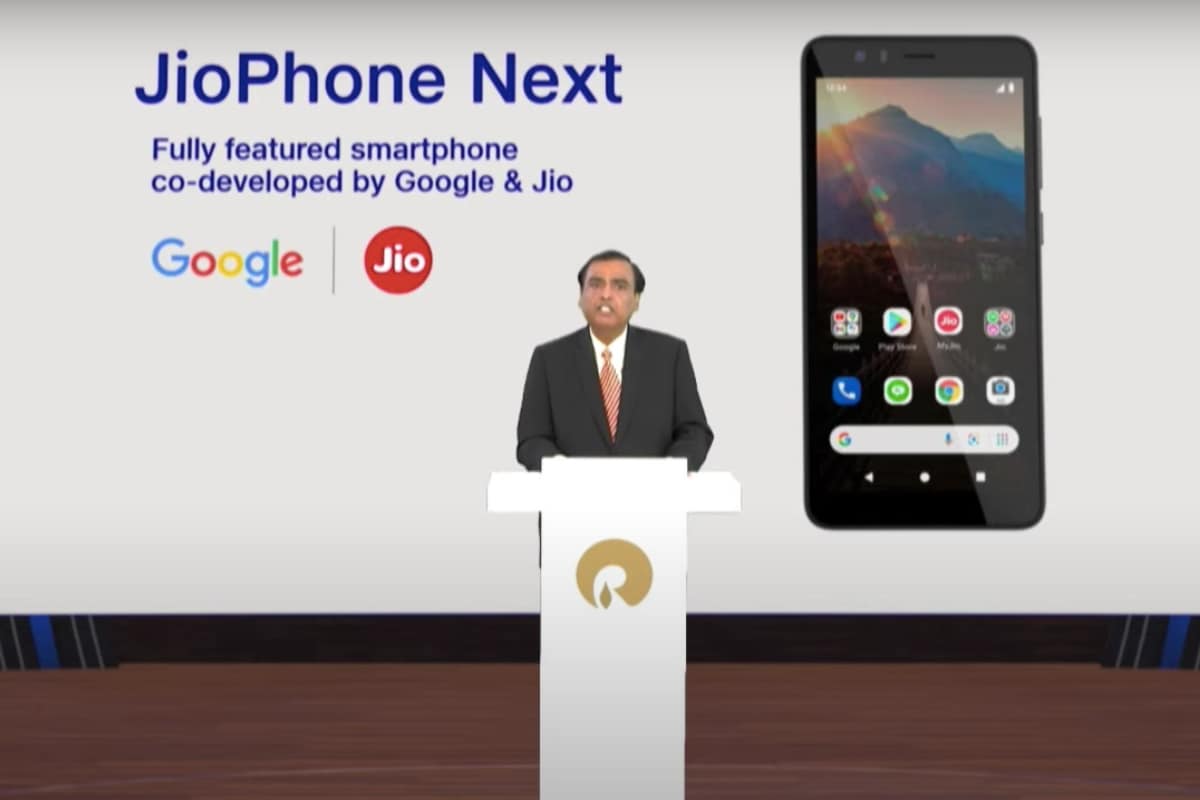

A smartphone widely believed to be priced below $50 (roughly Rs. 3,650), likely the world’s cheapest, will start selling a week from now. If Mukesh Ambani’s JioPhone Next, an Android device custom-built for India by Alphabet’s Google, is a hit in the price-conscious market, it will solve one problem for banks while posing another. With the country’s remaining 300 million feature-phone users going online, there will be a surge of customer data that can stand in for collateral. The question is, how will banks get their hands on it?

An answer has come from iSPIRT, a small band of policy influencers quietly setting up technology standards for India’s digital markets, inducing firms to enter new, open-network markets from online payments to healthcare.

The Bangalore-based group is championing a fresh set of players — account aggregators — to unlock a much sought-after prize: Bringing into the folds of formal credit the 80 percent of adults in developing countries (40 percent in rich nations) who don’t borrow money from traditional institutions.

But these people and their micro enterprises are increasingly online thanks to innovations like JioPhone Next. They’re paying rents, rates and utility bills and receiving payments on their smartphones, scattering their footprints all over the Internet. Account aggregators will gather those digital crumbs for people to share their own data in a machine-readable format for a bank loan application.

Introducing a layer of consent managers is important. Emerging-market borrowers can have many types of accounts-based relationships. Yet they can be useless to banks if they can’t present a composite picture of their financial lives to access formal loans that get monitored by credit bureaus. More than three-fifths of India’s adult population is either invisible to credit scorers or not considered worth the trouble by standard lending institutions.

In an advanced economy like the US, services such as Experian Boost and LenddoScore help narrow the subprime borrowers’ visibility gap by getting them to voluntarily submit their utility or video-streaming bills to demonstrate creditworthiness. But in an emerging market with low financial literacy, banks would rather leave the bottom of the pyramid to lenders who know the borrower in real life or have some social leverage on her — such as micro-finance firms that lend to groups of women.

Conversely, tech platforms, intimately aware of their customers’ online behaviour, can match them with loans, collecting fees while leaving risks with the banks. Jack Ma’s Ant cornered nearly a fifth of China’s short-term consumer debt before Beijing broke up the game.

Not every country can afford to bring out the heavy artillery against its private sector: Politics wouldn’t allow it. Aggregators can be a much softer tool for keeping the lending market fair, giving banks a reasonable economic chance to compete with data-rich tech giants.

Take JioPhone Next. It will spew out data about a large segment of sparsely banked population. Jio, Ambani’s 4G telecom network, will capture some of it as subscribers of its cheap data plans buy groceries from JioMart, an online partnership with neighborhood stores across India. Google will also get valuable data about users’ location and search queries. Facebook will exploit its own knowledge, as the social media giant adds to its half-a-billion-strong Indian customer base for WhatsApp and a growing craze for Instagram Reels, a video-sharing platform. Unsurprisingly then, Google wants to influence India’s deposit market, and Facebook is nibbling into the small business loans pie.

When it comes to real-time data, banks can never match the platforms’ clout. But account aggregators’ snapshots can help them catch a break.

Just enough additional data that will tell them if a customer is more creditworthy than suggested by a low (or no) credit score can make a big difference to profit, especially as banks won’t have to pay hefty fees to the likes of Jio, Google or Facebook for their proprietary assessments. By owning and explicitly sharing their data, customers will avoid getting trapped in the tech industry’s biased algorithms. Tiny enterprises will be able to show their cash flows to lenders by pooling everything from tax payments to customer receipts. Once telecom firms come on board, an affordable “buy-now-pay-later” plan on a refrigerator purchase will become possible for a low-income family that pays its phone bills regularly .

Aggregation, being a utility, will be like tap water to platforms’ Evian, and be priced accordingly. Who will own the pipes? Walmar’s PhonePe, which runs India’s most popular digital wallet, has received an in-principle approval to be an aggregator from the central bank. Eight banks, which between them account for 48 percent of all accounts in the country, have agreed to use the framework, which went live Thursday.

It’s a good start. Banks desperately need some help to stay in the money game. Or they’ll just go crying to regulators and ask them for special protections against Big Tech. That would hurt experimentation and delay the credit revolution that $50 (roughly Rs. 3,650) phones can unleash.

© 2021 Bloomberg LP