![]() Part II. Technical details (PDF)

Part II. Technical details (PDF)

UEFI (or Unified Extensible Firmware Interface) has become a prominent technology that is embedded within designated chips on modern day computer systems. Replacing the legacy BIOS, it is typically used to facilitate the machine’s boot sequence and load the operating system, while using a feature-rich environment to do so. At the same time, it has become the target of threat actors to carry out exceptionally persistent attacks.

One such attack has become the subject of our research, where we found a compromised UEFI firmware image that contained a malicious implant. This implant served as means to deploy additional malware on the victim computers, one that we haven’t come across thus far. To the best of our knowledge, this is the second known public case where malicious UEFI firmware in use by a threat actor was found in the wild.

Throughout this blog we will elaborate on the following key findings:

- We discovered rogue UEFI firmware images that were modified from their benign counterpart to incorporate several malicious modules;

- The modules were used to drop malware on the victim machines. This malware was part of a wider malicious framework that we dubbed MosaicRegressor;

- Components from that framework were discovered in a series of targeted attacks pointed towards diplomats and members of an NGO from Africa, Asia and Europe, all showing ties in their activity to North Korea;

- Code artefacts in some of the framework’s components and overlaps in C&C infrastructure used during the campaign suggest that a Chinese-speaking actor is behind these attacks, possibly having connections to groups using the Winnti backdoor;

The attack was found with the help of Firmware Scanner, which has been integrated into Kaspersky products since the beginning of 2019. This technology was developed to specifically detect threats hiding in the ROM BIOS, including UEFI firmware images.

Current State of the Art

Before we dive deep into our findings, let us have a quick recap of what UEFI is and how it was leveraged for attacks thus far. In a nutshell, UEFI is a specification that constitutes the structure and operation of low-level platform firmware, so as to allow the operating system to interact with it at various stages of its activity.

This interaction happens most notably during the boot phase, where UEFI firmware facilitates the loading of the operating system itself. That said, it can also occur when the OS is already up and running, for example in order to update the firmware through a well-defined software interface.

Considering the above, UEFI firmware makes for a perfect mechanism of persistent malware storage. A sophisticated attacker can modify the firmware in order to have it deploy malicious code that will be run after the operating system is loaded. Moreover, since it is typically shipped within SPI flash storage that is soldered to the computer’s motherboard, such implanted malware will be resistant to OS reinstallation or replacement of the hard drive.

This type of attack has occurred in several instances in the past few years. A prominent example is the LowJax implant discovered by our friends at ESET in 2018, in which patched UEFI modules of the LoJack anti-theft software (also known as Computrace) were used to deploy a malicious user mode agent in a number of Sofacy Fancy Bear victim machines. The dangers of Computrace itself were described by our colleagues from the Global Research and Analysis Team (GReAT) back in 2014.

Another example is source code of a UEFI bootkit named VectorEDK which was discovered in the Hacking Team leaks from 2015. This code consisted of a set of UEFI modules that could be incorporated into the platform firmware in order to have it deploy a backdoor to the system which will be run when the OS loads, or redeploy it if it was wiped. Despite the fact that VectorEDK’s code was made public and can be found in Github nowadays, we hadn’t witnessed actual evidence of it in the wild, before our latest finding.

Our Discovery

During an investigation, we came across several suspicious UEFI firmware images. A deeper inspection revealed that they contained four components that had an unusual proximity in their assigned GUID values, those were two DXE drivers and two UEFI applications. After further analysis we were able to determine that they were based on the leaked source code of HackingTeam’s VectorEDK bootkit, with minor customizations.

Rogue components found within the compromised UEFI firmware

The goal of these added modules is to invoke a chain of events that would result in writing a malicious executable named ‘IntelUpdate.exe’ to the victim’s Startup folder. Thus, when Windows is started the written malware would be invoked as well. Apart from that, the modules would ensure that if the malware file is removed from the disk, it will be rewritten. Since this logic is executed from the SPI flash, there is no way to avoid this process other than eliminating the malicious firmware.

Following is an outline of the components that we revealed:

- SmmInterfaceBase: a DXE driver that is based on Hacking Team’s ‘rkloader’ component and intended to deploy further components of the bootkit for later execution. This is done by registering a callback that will be invoked upon an event of type EFI_EVENT_GROUP_READY_TO_BOOT. The event occurs at a point when control can be passed to the operating system’s bootloader, effectively allowing the callback to take effect before it. The callback will in turn load and invoke the ‘SmmAccessSub’ component.

- Ntfs: a driver written by Hacking Team that is used to detect and parse the NTFS file system in order to allow conducting file and directory operations on the disk.

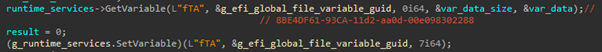

- SmmReset: a UEFI application intended to mark the firmware image as infected. This is done by setting the value of a variable named ‘fTA’ to a hard-coded GUID. The application is based on a component from the original Vector-EDK code base that is named ‘ReSetfTA’.

Setting of the fTA variable with a predefined GUID to mark the execution of the bootkit

- SmmAccessSub: the main bootkit component that serves as a persistent dropper for a user-mode malware. It is executed by the callback registered during the execution of ‘SmmInterfaceBase’, and takes care of writing a binary embedded within it as a file named ‘IntelUpdate.exe’ to the startup directory on disk. This allows the binary to execute when Windows is up and running.

This is the only proprietary component amongst the ones we inspected, which was mostly written from scratch and makes only slight use of code from a Vector-EDK application named ‘fsbg’. It conducts the following actions to drop the intended file to disk:- Bootstraps pointers for the SystemTable, BootServices and RuntimeServices global structures.

- Tries to get a handle to the currently loaded image by invoking the HandleProtocol method with the EFI_LOADED_IMAGE_PROTOCOL_GUID argument.

- If the handle to the current image is obtained, the module attempts to find the root drive in which Windows is installed by enumerating all drives and checking that the ‘\Windows\System32’ directory exists on them. A global EFI_FILE_PROTOCOL object that corresponds to the drive will be created at this point and referenced to open any further directories or files in this drive.

- If the root drive is found in the previous stage, the module looks for a marker file named ‘setupinf.log’ under the Windows directory and proceeds only if it doesn’t exist. In the absence of this file, it is created.

- If the creation of ‘setupinf.log’ succeeds, the module goes on to check if the ‘Users’ directory exists under the same drive.

- If the ‘Users’ directory exists, it writes the ‘IntelUpdate.exe’ file (embedded in the UEFI application’s binary) under the ‘ProgramData\Microsoft\Windows\Start Menu\Programs\Startup’ directory in the root drive.

Code from ‘SmmAccessSub’ used to write the embedded ‘IntelUpdate.exe’ binary to the Windows Startup directory

Unfortunately, we were not able to determine the exact infection vector that allowed the attackers to overwrite the original UEFI firmware. Our detection logs show that the firmware itself was found to be malicious, but no suspicious events preceded it. Due to this, we can only speculate how the infection could have happened.

One option is through physical access to the victim’s machine. This could be partially based on Hacking Team’s leaked material, according to which the installation of firmware infected with VectorEDK requires booting the target machine from a USB key. Such a USB would contain a special update utility that can be generated with a designated builder provided by the company. We found a Q-flash update utility in our inspected firmware, which could have been used for such a purpose as well.

Furthermore, the leaks reveal that the UEFI infection capability (which is referred to by Hacking Team as ‘persistent installation’) was tested on ASUS X550C laptops. These make use of UEFI firmware by AMI which is very similar to the one we inspected. For this reason we can assume that Hacking Team’s method of patching the firmware would work in our case as well.

Excerpt from a Hacking Team manual for deployment of infected UEFI firmware, also known as ‘persistent installation’

Of course, we cannot exclude other possibilities whereby rogue firmware was pushed remotely, perhaps through a compromised update mechanism. Such a scenario would typically require exploiting vulnerabilities in the BIOS update authentication process. While this could be the case, we don’t have any evidence to support it.

The Bigger Picture: Enter MosaicRegressor Framework

While Hacking Team’s original bootkit was used to write one of the company’s backdoors to disk, known as ‘Soldier’, ‘Scout’ or ‘Elite’, the UEFI implant we investigated deployed a new piece of malware that we haven’t seen thus far. We decided to look for similar samples that share strings and implementation traits with the dropped binary. Consequently, the samples that we found suggested that the dropped malware was only one variant derived from a wider framework that we named MosaicRegressor.

MosaicRegressor is a multi-stage and modular framework aimed at espionage and data gathering. It consists of downloaders, and occasionally multiple intermediate loaders, that are intended to fetch and execute payload on victim machines. The fact that the framework consists of multiple modules assists the attackers to conceal the wider framework from analysis, and deploy components to target machines only on demand. Indeed, we were able to obtain only a handful of payload components during our investigation.

The downloader components of MosaicRegressor are composed of common business logic, whereby the implants contact a C&C, download further DLLs from it and then load and invoke specific export functions from them. The execution of the downloaded modules usually results in output that can be in turn issued back to the C&C.

Having said that, the various downloaders we observed made use of different communication mechanisms when contacting their C&Cs:

- CURL library (HTTP/HTTPS)

- BITS transfer interface

- WinHTTP API

- POP3S/SMTPS/IMAPS, payloads transferred in e-mail messages

The last variant in the list is distinct for its use of e-mail boxes to host the requested payload. The payload intended to run by this implant can also generate an output upon invocation, which can be later forwarded to a ‘feedback’ mail address, where it will likely be collected by the attackers.

The mail boxes used for this purpose reside on the ‘mail.ru’ domain, and are accessed using credentials that are hard-coded in the malware’s binary. To fetch the requested file from the target inbox, MailReg enters an infinite loop where it tries to connect to the “pop.mail.ru” server every 20 minutes, and makes use of the first pair of credentials that allow a successful connection. The e-mails used for login (without their passwords) and corresponding feedback mail are specified in the table below:

| Login mail | Feedback mail |

| thtgoolnc@mail.ru | thgetmmun@mail.ru |

| thbububugyhb85@mail.ru | thyhujubnmtt67@mail.ru |

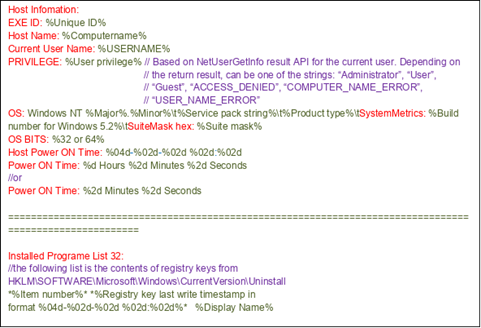

The downloaders can also be split in two distinct types, the “plain” one just fetching the payload, and the “extended” version that also collects system information:

Structure of the log file written by BitsRegEx, strings marked in red are the original fields that appear in that file

We were able to obtain only one variant of the subsequent stage, that installs in the autorun registry values and acts as another loader for the components that are supposed to be fetched by the initial downloader. These components are also just intermediate loaders for the next stage DLLs. Ultimately, there is no concrete business logic in the persistent components, as it is provided by the C&C server in a form of DLL files, most of them temporary.

We have observed one such library, “load.rem“, that is a basic document stealer, fetching files from the “Recent Documents” directory and archiving them with a password, likely as a preliminary step before exfiltrating the result to the C&C by another component.

The following figure describes the full flow and connection between the components that we know about. The colored elements are the components that we obtained and gray ones are the ones we didn’t:

Flow from BitsRegEx to execution of intermediate loaders and final payload

Who were the Targets?

According to our telemetry, there were several dozen victims who received components from the MosaicRegressor framework between 2017 and 2019. These victims included diplomatic entities and NGOs in Africa, Asia and Europe. Only two of them were also infected with the UEFI bootkit in 2019, predating the deployment of the BitsReg component.

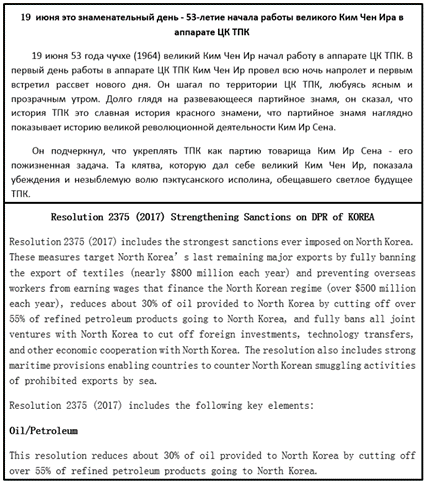

Based on the affiliation of the discovered victims, we could determine that all had some connection to the DPRK, be it non-profit activity related to the country or actual presence within it. This common theme can be reinforced through one of the infection vectors used to deliver the malware to some of the victims, which was SFX archives pretending to be documents discussing various subjects related to North Korea. Those were bundled with both an actual document and MosaicRegressor variants, having both executed when the archive is opened. Examples for the lure documents can be seen below.

Examples of lure documents bundled to malicious SFX archives sent to MosaicRegressor victims, discussing DPRK related topics

Who is behind the attack?

When analyzing MosaicRegressor’s variants, we noticed several interesting artefacts that provided us with clues on the identity of the actor behind the framework. As far as we can tell, the attacks were conducted by a Chinese-speaking actor, who may have previously used the Winnti backdoor. We found the following evidence to support this:

- We spotted many strings used in the system information log generated by the BitsRegEx variant that contain the character sequence ‘0xA3, 0xBE’. This is an invalid sequence for a UTF8 string and the LATIN1 encoding translates these symbols to a pound sign followed by a “masculine ordinal indicator” (“£º”). An attempt to iterate over all available iconv symbol tables, trying to convert the sequence to UTF-8, produces possible candidates that give a more meaningful interpretation. Given the context of the string preceding the symbol and line feed symbols following it, the best match is the “FULL-WIDTH COLON” Unicode character translated from either the Chinese or Korean code pages (i.e. CP936 and CP949).

Figure: The BitsRegEx system information log making use of the character sequence 0xA3, 0xBA, likely used to represent a full-width colon, according to code pages CP936 and CP949.

- Another artefact that we found was a file resource found in CurlReg samples that contained a language identifier set to 2052 (“zh-CN”)

Chinese language artefact in the resource section of a CurlReg sample

- We detected an OLE2 object taken out of a document armed with the CVE-2018-0802 vulnerability, which was produced by the so-called ‘Royal Road’ / ‘8.t’ document builder and used to drop a CurlReg variant. To the best of our knowledge, this builder is commonly used by Chinese-speaking threat actors.

Excerpt from the OLE2 object found within a ‘Royal Road’ weaponized document, delivering the CurlReg variant

- A C&C address (103.82.52[.]18) which was found in one of MosaicRegressor’s variants (MD5:3B58E122D9E17121416B146DAAB4DB9D) was observed in use by the ‘Winnti umbrella and linked groups’, according to a publicly available report. Since this is the only link between our findings and any of the groups using the Winnti backdoor, we estimate with low confidence that it is indeed responsible for the attacks.

Conclusion

The attacks described in this blog post demonstrate the length an actor can go in order to gain the highest level of persistence on a victim machine. It is highly uncommon to see compromised UEFI firmware in the wild, usually due to the low visibility into attacks on firmware, the advanced measures required to deploy it on a target’s SPI flash chip, and the high stakes of burning sensitive toolset or assets when doing so.

With this in mind, we see that UEFI continues to be a point of interest to APT actors, while at large being overlooked by security vendors. The combination of our technology and understanding of the current and past campaigns leveraging infected firmware, helps us monitor and report on future attacks against such targets.

The full details of this research, as well as future updates on the underlying threat actor, are available to customers of the APT reporting service through our Threat Intelligence Portal.

IoCs

UEFI Modules

F5B320F7E87CC6F9D02E28350BB87DE6 (SmmInterfaceBase)

B53880397D331C6FE3493A9EF81CD76E (SmmAccessSub)

91A473D3711C28C3C563284DFAFE926B (SmmReset)

DD8D3718197A10097CD72A94ED223238 (Ntfs)

RAR SFX droppers

0EFB785C75C3030C438698C77F6E960E

12B5FED367DB92475B071B6D622E44CD

3B3BC0A2772641D2FC2E7CBC6DDA33EC

3B58E122D9E17121416B146DAAB4DB9D

70DEF87D180616406E010051ED773749

7908B9935479081A6E0F681CCEF2FDD9

AE66ED2276336668E793B167B6950040

B23E1FE87AE049F46180091D643C0201

CFB072D1B50425FF162F02846ED263F9

Decoy documents

0D386EBBA1CCF1758A19FB0B25451AFE

233B300A58D5236C355AFD373DABC48B

449BE89F939F5F909734C0E74A0B9751

67CF741E627986E97293A8F38DE492A7

6E949601EBDD5D50707C0AF7D3F3C7A5

92F6C00DA977110200B5A3359F5E1462

A69205984849744C39CFB421D8E97B1F

D197648A3FB0D8FF6318DB922552E49E

BitsReg

B53880397D331C6FE3493A9EF81CD76E

AFC09DEB7B205EADAE4268F954444984 (64-bit)

BitsRegEx

DC14EE862DDA3BCC0D2445FDCB3EE5AE

88750B4A3C5E80FD82CF0DD534903FC0

C63D3C25ABD49EE131004E6401AF856C

D273CD2B96E78DEF437D9C1E37155E00

72C514C0B96E3A31F6F1A85D8F28403C

CurlReg

9E182D30B070BB14A8922CFF4837B94D

61B4E0B1F14D93D7B176981964388291

3D2835C35BA789BD86620F98CBFBF08B

CurlRegEx

328AD6468F6EDB80B3ABF97AC39A0721

7B213A6CE7AB30A62E84D81D455B4DEA

MailReg

E2F4914E38BB632E975CFF14C39D8DCD

WinHTTP Based Downloaders

08ECD8068617C86D7E3A3E810B106DCE

1732357D3A0081A87D56EE1AE8B4D205

74DB88B890054259D2F16FF22C79144D

7C3C4C4E7273C10DBBAB628F6B2336D8

BitsReg Payload (FileA.z)

89527F932188BD73572E2974F4344D46

2nd Stage Loaders

36B51D2C0D8F48A7DC834F4B9E477238 (mapisp.dll)

1C5377A54CBAA1B86279F63EE226B1DF (cryptui.sep)

9F13636D5861066835ED5A79819AAC28 (cryptui.sep)

3rd Stage Payload

FA0A874926453E452E3B6CED045D2206 (load.rem)

File paths

%APPDATA%\Microsoft\Credentials\MSI36C2.dat

%APPDATA%\Microsoft\Internet Explorer\%Computername%.dat

%APPDATA%\Microsoft\Internet Explorer\FileA.dll

%APPDATA%\Microsoft\Internet Explorer\FileB.dll

%APPDATA%\Microsoft\Internet Explorer\FileC.dll

%APPDATA%\Microsoft\Internet Explorer\FileD.dll

%APPDATA%\Microsoft\Internet Explorer\FileOutA.dat

%APPDATA%\Microsoft\Network\DFileA.dll

%APPDATA%\Microsoft\Network\DFileC.dll

%APPDATA%\Microsoft\Network\DFileD.dll

%APPDATA%\Microsoft\Network\subst.sep

%APPDATA%\Microsoft\WebA.dll

%APPDATA%\Microsoft\WebB.dll

%APPDATA%\Microsoft\WebC.dll

%APPDATA%\Microsoft\Windows\LnkClass.dat

%APPDATA%\Microsoft\Windows\SendTo\cryptui.sep

%APPDATA%\Microsoft\Windows\SendTo\load.dll %APPDATA%\Microsoft\Windows\load.rem

%APPDATA%\Microsoft\Windows\mapisp.dll

%APPDATA%\Microsoft\exitUI.rs

%APPDATA%\Microsoft\sppsvc.tbl

%APPDATA%\Microsoft\subst.tbl

%APPDATA%\newplgs.dll

%APPDATA%\rfvtgb.dll

%APPDATA%\sdfcvb.dll

%APPDATA%\msreg.dll

%APPDATA\Microsoft\dfsadu.dll

%COMMON_APPDATA%\Microsoft\Windows\user.rem

%TEMP%\BeFileA.dll

%TEMP%\BeFileC.dll

%TEMP%\RepairA.dll

%TEMP%\RepairB.dll

%TEMP%\RepairC.dll

%TEMP%\RepairD.dll

%TEMP%\wrtreg_32.dll

%TEMP%\wrtreg_64.dll

%appdata%\dwhost.exe

%appdata%\msreg.exe

%appdata%\return.exe

%appdata%\winword.exe

Domains and IPs

103.195.150.106

103.229.1.26

103.243.24.171

103.243.26.211

103.30.40.116

103.30.40.39

103.39.109.239

103.39.109.252

103.39.110.193

103.56.115.69

103.82.52.18

117.18.4.6

144.48.241.167

144.48.241.32

150.129.81.21

43.252.228.179

43.252.228.252

43.252.228.75

43.252.228.84

43.252.230.180

menjitghyukl.myfirewall.org

Additional Suspected C&Cs

43.252.230.173

185.216.117.91

103.215.82.161

103.96.72.148

122.10.82.30

Mutexes

FindFirstFile Message Bi

set instance state

foregrounduu state

single UI

Office Module

process attach Module