For many people, seeing a lot of old people in a hospital is something expected, even mundane. But for Dr Kanapon Phumratprapin, it was a challenge that he wanted to help solve.

The result of his effort was Health at Home, a Thai startup that integrates geriatric medical practice and digital technology to find caregivers for elderly patients.

While working in a Bangkok hospital many years ago, he noticed that most elderly patients who had been admitted wanted to go home. But they couldn’t, even when their medical condition was not serious enough to warrant a hospital stay. It was not easy to find good, qualified caregivers to look after them at home.

“Are there any ways to keep them out of the hospitals?” he recalled asking himself.

That led him to establish Health at Home in 2015 — a few years after Asia-rooted mobile applications such as Grab and Line were launched, spurring a new wave of consumer adoption of services on digital platforms.

After successfully obtaining seed funding from the now-defunct Dtac Accelerate programme, Dr Kanapon together with his team developed an algorithm that matches patients with CarePro, experienced professional caregivers trained and certified by Health at Home.

Getting help from CarePro requires only a few steps: filling out a form on the Health at Home Line app, choosing a date and location, selecting a CarePro profile, and paying. It takes around one to four hours to match a caregiver and a patient.

All these steps can be done on a mobile phone, which is a change from the traditional method of sourcing caregivers. For many families, this has involved seeking recommendations from friends, which can take days to set up a contact, and there is no guarantee of getting a qualified person.

Since Health at Home was launched, revenues and user numbers have been rising by 20-30% a year, according to Dr Kanapon.

“With technology, the future of healthcare delivery will likely happen outside hospitals,” he said. “But healthcare is not only about technology. It’s also about users’ acceptance and requirements. It is about timing.”

Health at Home is part of a large pool of Asian startups that have emerged to tackle everyday problems and grasp opportunities from the region’s growing technology market and high technology adoption by consumers.

From advanced to developing countries, across sectors, technology has become deeply integrated into Asia’s economy. It is poised to play an outsize role in future growth — and also created a challenge for those that are struggling to catch up.

According to a recent report by the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI), “The Future of Asia: How Asia can boost growth through technology leapfrogging”, the region accounted for a 52% share of the global growth in technology company revenues during the past decade.

Asia has undergone a technological transformation that has resulted in a substantial increase in startup funding, accounting for 43% of the global share, spending on research and development (51%), and the number of patents filed (87%).

The report points out that 50% of Asia’s gross domestic product (GDP) growth between 2010 and 2020, equivalent to US$6 trillion, came from total factor productivity — a broad measure of the contribution to the economy of technology and innovation. If Asia wants to maintain 4% annual growth until 2030, around 43% of this growth, equivalent to $7 trillion, will have to come from technology, it says.

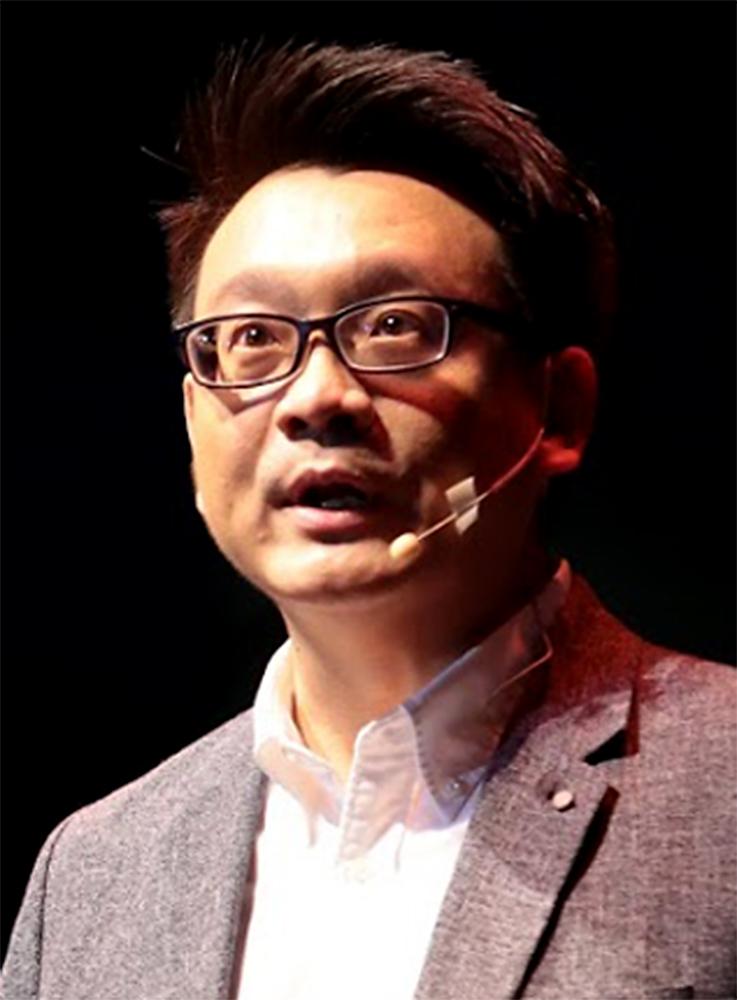

Dr Kanapon Phumratprapin (centre), developed the Health at Home portal to match elderly patients with skilled, professional caregivers. SUPPLIED

FASTER ACCELERATION

“It’s not just about technology. It’s also about the consumer adoption of technology,” said Anand Swaminathan, the leader of McKinsey Digital in Asia and a co-author of the MGI report.

According to the research conducted by his team, more than half of global internet users are in Asia. Around 41% of mobile app downloads are in the region, while its e-commerce volume is three times that of the United States.

This means that Asian consumer adoption of technology is “exponentially high”, Mr Swaminathan said, adding that acceleration will happen in specific areas such as mobile services, 5G, artificial intelligence (AI), and Internet of Things (IoT) applications.

“Technology and innovation in Asia are driving the fundamental core and changes in growth,” he said. “It’s actually changing the way consumers behave and consumer patterns. I think we are going to see acceleration. We are not going to see this slow down.”

During the Covid-19 pandemic, the acceleration got even faster as the necessity of social distancing caused people to spend more time on the internet and purchase more services and goods online.

Research by Google, Temasek Holdings and Bain & Company shows that 40 million new internet users emerged in Southeast Asia last year, bringing the region’s total to 400 million in a population of about 660 million. More than one in three consumers of digital services were new to them, they noted.

Consumers’ rising technology adoption has led many tech firms, on varying scales, to thrive during the pandemic.

Tencent, the world’s largest video game vendor based in China, reported its revenue climbed 29% in the third quarter of last year, fuelled by rising demand for gaming and advertising during the lockdown.

M-Service, the company running Vietnam’s biggest e-wallet company MoMo, recently raised over $100 million from global investors, including Goodwater Capital and Warburg Pincus, as part of its plan to become a super-app.

Even in the entertainment industry, the South Korean firm behind the pop superstars BTS, Big Hit Entertainment, increased profits last year by selling online concert tickets, multimedia content, albums and merchandise via its Weverse Shop app downloaded by nearly 2 million users worldwide.

However, there is still a considerable technology gap between advanced and developing countries, while the ways in which technology-based business has developed in cities also tends to vary.

The McKinsey report indicates that China and India are home to more than two-thirds of Asia’s urban technology hot spots. Both countries account for 49% of global tech companies’ expansion into Asia.

“Each city has a different consumer adoption and consumer pattern. But also, they have different technologies they have access to,” Mr Swaminathan pointed out. “I do believe that each country plays a different role in how they think about technology.”

Many cities across Asia have created technology-based manufacturing hubs, such as in Taiwan and Singapore. On the other hand, Bangkok and Kuala Lumpur have become business-to-business enterprise technology hotspots. Mr Swaminathan sees this as a complement to the business-to-consumer technology-driven companies in China and India.

DEFENDING AND ATTACKING

Along with consumers and businesses, governments in Asian countries that have witnessed digital acceleration during the pandemic have come up with new strategies to lay foundations for future economic growth.

“Covid-19 spread a shock that caused twin economic and health crises. But it also opened a window for governments to review policies and adjust them to seize future opportunities,” said Veerayooth Kanchoochat, an associate professor at the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies, based in Tokyo.

The government of South Korean President Moon Jae-in, for example, has announced an ambitious “Korean New Deal” that is built on two pillars: a Digital New Deal and a Green New Deal.

It has set aside a budget of 60 trillion won ($54 billion) over the next five years to strengthen digital capacity and competitiveness while making a transition to a net-zero emissions economy. Its plans include building 5G infrastructure and cloud computing for the government, and accelerating the industrial adoption of 5G and AI.

A similar move is under way in Singapore, where the government increased its information and communication technology procurement budget during the pandemic, and is offering grants to companies and even local retailers to digitise their businesses.

In Taiwan, President Tsai Ing-wen last year introduced six “core strategic industries”, setting a target to transform the already well advanced island republic into a centre for high-technology manufacturing, research and development, and green energy.

The six industries are information and digital technology, cybersecurity, medical technology and precision health, green and renewable energy, national defence and strategic industries, and strategic stockpile industries.

“It’s not just about technology. It’s also about the consumer adoption of technology,” says Anand Swaminathan, leader of McKinsey Digital in Asia. SUPPLIED

“All these policies reflect a good combination of flexibility and decisiveness that the adaptive governments of East Asia possess,” said Mr Veerayooth, who studies political and economic development in Asia and was an economic adviser to the now-dissolved Future Forward Party in Thailand. But he questions whether some developing countries will be able to do the same.

For example, the Thai government announced the Thailand 4.0 strategy in 2015 to depart from its manufacturing and export dependence (or economy 3.0) to a value-based economy driven by technology and innovation. But its progress has been spotty, especially during the pandemic when the government has been compelled to adopt a short-term focus on health and economic relief measures.

“The main challenge would be how to link a 4.0 industry with an existing one, that is the 3.0 manufacturing that Thailand already has,” Mr Veerayooth said, adding that most countries that have succeeded in driving technology and innovation have built a new economy on a foundation of strong existing industries.

“Developing countries like Thailand (as technology buyers) should clearly divide their strategy between defending and attacking,” he said.

Defending is about finding ways to properly regulate outflows as well as increasing data capacity and revenues of technology companies, and adjusting laws to suit changing realities in the digital world.

Legal reform includes protecting the people who power the tech companies’ pursuit of revenue. The hundreds of thousands of drivers who toil for the likes of Grab and Gojek are a prime example. By calling them “partners” and treating them as contractors and not employees, the companies are not obliged to provide any of the welfare or benefits specified in existing labour laws.

Veerayooth Kanchoochat, associate professor at the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies in Tokyo

Attacking is about providing an environment conducive to taking entrepreneurial risks and learning through trial and error. Mistakes are the real source of innovation.

“Defending is more important in the short and medium term. Because it involves a lot of people, especially labourers who need to work harder and take more risks amid the pandemic,” Mr Veerayooth noted.

“When it comes to policymaking, we would do better to think about the backward and forward linking of value and employment, rather than an obsession with creating a new unicorn — which even if it’s successful in the end, it may not deliver anything meaningful to the local economy,” he added.