Job losses in the next 10 years will effectively be matched by even greater job creation.

image: Getty Images/iStockphotoNew technologies will lead to tens of millions of job vacancies by 2030, according to the latest economic analysis from Boston Consulting Group (BCG). But that does little to erase the threat of unemployment spiking due to the automation of labour, BCG says.

BCG’s economists carried out detailed modelling of the prospective changes in the supply and demand of labour in Germany, Australia and the US, and found that job losses in the next 10 years will effectively be matched by even greater job creation. The problem is that those who find themselves out of a job won’t necessarily be those that employers are looking to hire.

Eliminating 10 million jobs and creating the same number of new jobs might appear to have a negligible impact, the researchers say; but in fact, doing so represents huge economic disruption, both at a national level and for the people whose jobs are at stake.

SEE: Guide to Becoming a Digital Transformation Champion (TechRepublic Premium)

“It is important to not just focus on the overall net surplus or shortfall because behind the net change, there are significant supply-demand mismatches across job types and geographical location,” Miguel Carrasco, senior partner at BCG, tells ZDNet. “It is unrealistic to expect perfect exchangeability — not all of the surplus capacity in the workforce can be redeployed to meet new or growing demand.”

To understand how employment might change to 2030, BCG’s researchers assessed various factors that might affect a country’s workforce. They accounted for numbers likely to enter the job market (college graduates, migration patterns) and those projected to leave (retirement and mortality rates).

They then pitted those numbers against various scenarios representing how demand for labour might change, based on expected GDP growth, as well as potential technology adoption rates. In short, the higher a country’s growth, the more likely it is that jobs will be created. Technology adoption, meanwhile, might cause some work to be eliminated as a result of automation, while also creating new employment opportunities.

In the midrange scenario – a baseline GDP growth and a medium rate of technology adoption – all three countries were projected to experience labour shortfalls. Germany could find itself in need of three million workers by 2030, and Australia one million short. In the US, the shortfall could surpass 17 million jobs.

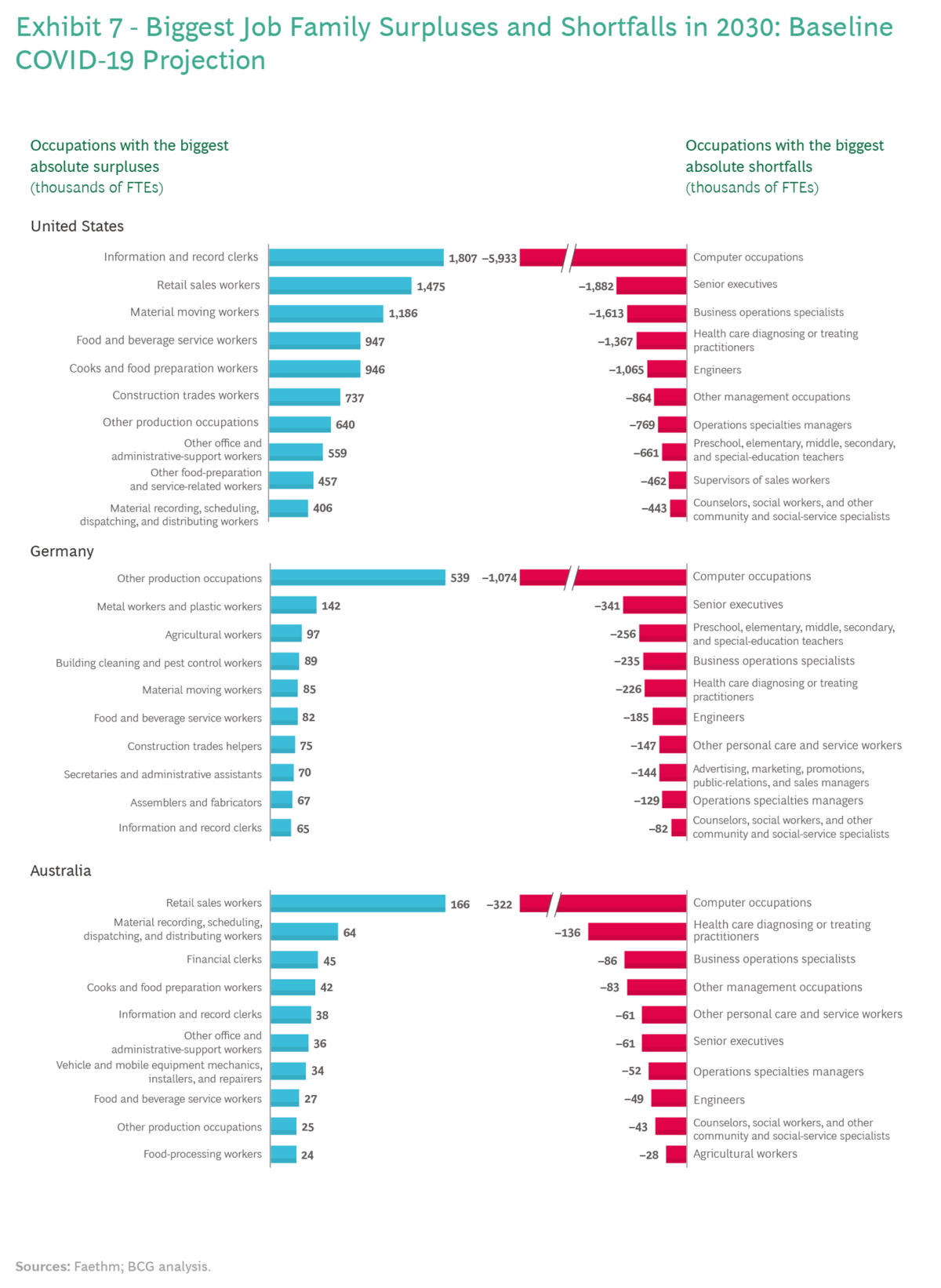

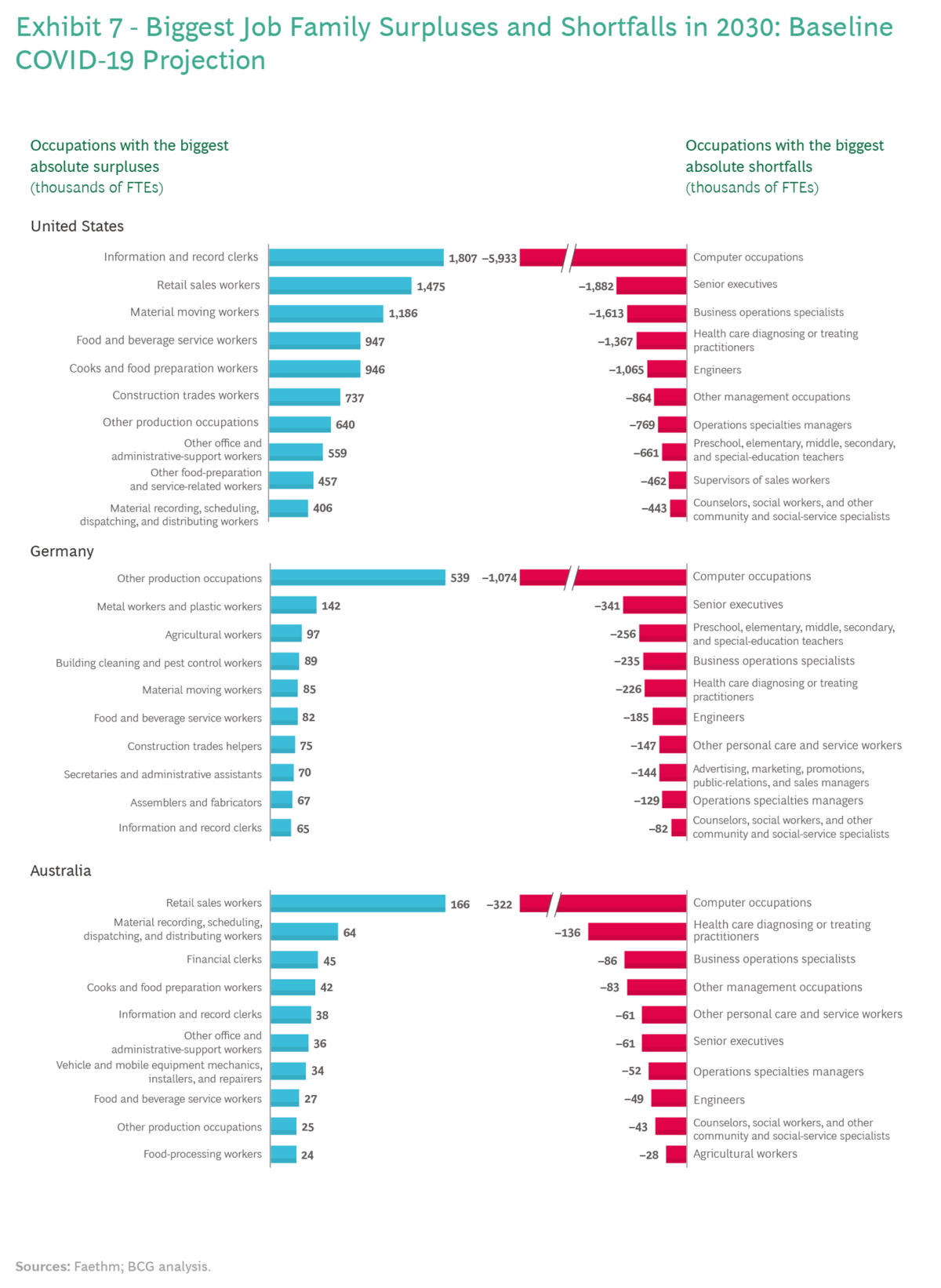

At the same time, technology will displace many workers. In the three countries studied, the projected labour surplus is significant, reaching almost 11 million workers in the US alone. Jobs most likely to be affected will be in office and administrative support, as well as food preparation and services; in Germany, production workers will be those most affected by the automation of labour; and in Australia, job surpluses will most affect sales and related fields.

There is a clear mismatch between occupations that will be lost and those that will be in demand: in all three countries, the professions with the biggest looming shortfalls are computer-related occupations and jobs in science, technology, engineering and maths. Work that requires compassionate human interaction, including healthcare, social services or teaching, will also be in high demand.

There is a clear mismatch between occupations that will be lost and those that will be in demand.

Image: BCGThis is worrying, explain BCG’s specialists, who anticipate that as demand for talent is unmet, companies’ financial stability and ability to compete will be affected. “Labour shortages are more worrying for businesses and governments than a surplus of labour,” says Carrasco.

“Global businesses that are competing in the global market for the same talent will have a very limited pool of candidates to choose from. For governments, the handbrake labour shortages create will have a clear impact on economic growth.”

Up-skill and re-train for digital transformation

The solution? To aggressively up-skill and re-train the workforce, to ensure that demand for talent is met in time. Managing the workforce transition will require equipping those most at risk of job loss with the required skills to fill roles that are set to boom. This means creating future software developers, data analysts, or cybersecurity testers – but also developing skills such as empathy, imagination or creativity, which will underpin jobs in more social sectors.

The scope of the challenge is already immense: a survey conducted by the World Economic Forum in 2019 showed that only 27% of small companies and 29% of large companies believe they have the right talent for digital transformation.

As workers suddenly found themselves carrying out their jobs entirely online, the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted some critical and persistent knowledge gaps when it comes to digital skills. A global survey carried out by Salesforce, for example, showed that almost two-thirds of workers wished they had more up-to-date skill sets.

“The task of up-skilling and re-skilling the workforce is huge and urgent, but it is not insurmountable,” argues Carrasco. “It requires a concentrated and collaborative effort between governments, businesses and individuals.”

Governments will need to carry out better predictions of how their workforce will change over time, identifying where gaps will be created and building up-skilling programs at scale to respond to the problem.

SEE: What is Agile software development? Everything you need to know about delivering better code, faster

BCG’s report pointed to Singapore, where the government’s SkillsFuture program is designed to provide citizens with training opportunities to up-skill themselves. The program includes a ‘SkillsFuture Credit’ that provides funding for a person’s education over their lifetime. In 2020, the scheme reached 540,000 individual and 14,000 businesses.

Similarly, the Canadian government has created a platform called planext, to help residents see which occupations might correspond to their existing skills and chart a potential future career path, complete with opportunities for training and education.

The onus, however, will also be on companies to re-train their workforces by anticipating changes and providing their employees with opportunities for lifelong learning. According to the BCG report, investing in skills now will enable businesses to gain a significant competitive advantage, by ensuring that they have the right talent in the right place at the right time.

There are already some examples of early efforts: Australian supermarket giant Woolworths announced earlier this year that it was investing more than AU$50 million over the next three years to train more than 60,000 staff in new tech-related skills. The company’s staff – from stores, e-commerce operations, supply chain networks and support offices – will be trained in digital, data analytics, machine learning and robotics.