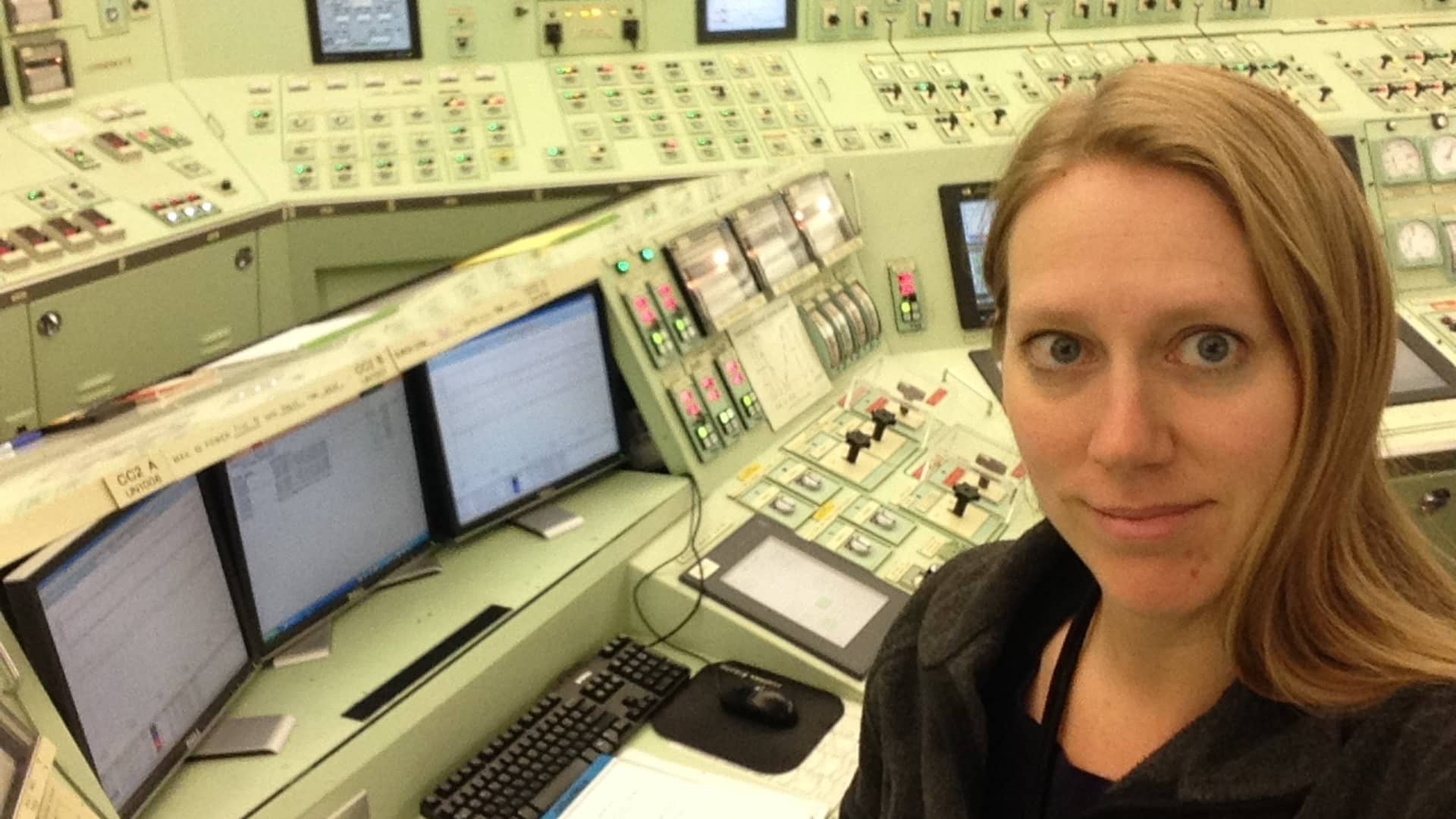

Heather Hoff was working in the control room of the Diablo Canyon nuclear plant near in San Luis Obispo County, Calif., when an earthquake caused a tsunami that shut off the power supply cooling three nuclear reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in Japan. Three nuclear reactor cores at Fukushima melted down.

“It was super scary,” Hoff told CNBC in a video interview. “It’s my worst nightmare as an operator — to be there and think about these other operators just across the ocean from us. They don’t know what’s going on with their plant. They have no power. They don’t know if people are hurt.”

In the first days after the accident, “what I was hearing on TV in the media was pretty scary,” Hoff said.

But as time passed and information about the meltdown became more available, the consequences of the accident became clear. While three employees who worked for the Tokyo Electric Power Company died because of the earthquake and resulting tsunami, nobody died because of the nuclear reactor accident.

“Three plants had meltdowns and that’s scary and horrible and expensive, but it didn’t really hurt anyone,” Hoff said. “And that was really surprising to me.”

In the wake of the Fukushima accident, Hoff went from fearing that she would need to leave her job to being committed to the potential of nuclear to be a safe, clean contribution to the global energy supply.

“Now I feel even more strongly that nuclear is the right thing to do and that the damaging parts about nuclear are actually not the technology itself, but our fear, our human responses to nuclear.”

After going through her own evolution in her thinking about nuclear energy, Hoff went on to co-found an advocacy group, Mothers for Nuclear, in 2016 with her colleague and friend Kristin Zaitz.

“There’s so much fear and so much misinformation… it’s a convenient villain,” Hoff said. “It’s okay to be scared, but that’s not the same thing as dangerous.”

Why Hoff started working at Diablo Canyon

Hoff did not anticipate her career in nuclear energy.

Hoff came to San Luis Obispo, Calif., to attend California Polytechnic State University, where she graduated in 2002 with a degree in materials engineering. After graduating, she worked “random jobs around town,” she said, including a clothing store, winery, and manufacturing animal thermometers for cows.

Hoff applied for and got a job as a plant operator at Diablo Canyonn in 2004. From the outset, Hoff was not sure what her job would entail and how she would feel about it, and her family was nervous about her taking a job working at a nuclear plant. So she decided to deal with the uncertainty by seeking out information herself.

“I’d heard a lot of stories of scary things — and just didn’t really know how I felt about nuclear,” Hoff told CNBC. “I spent the first probably six years of my career there asking tons and tons of questions.” For a while, she assumed it was only a matter of time before she would discover some “nefarious thing” happening at the nuclear reactor facility.

Her change in sentiment about nuclear energy was a gradual process. “I started feeling proud to work there, proud to help make such a huge quantity of clean electricity on a really small land footprint,” she told CNBC. Nuclear power actually is “in really good alignment with my environmental and humanitarian values,” she said.

As of now, Hoff has worked at Diablo Canyon for 18 years and she’s clear with herself that she’s a believer in the importance of nuclear energy.

From 2006 through 2008, Hoff took training classes from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to be able to operate the reactor. Now she writes operations and engineering procedures for Diablo Canyon, a job she’s had since 2014.

Diablo Canyon provides 8% of California’s total electricity and 15% of California’s carbon-free electricity, which is enough to power about 3 million homes, she told CNBC.

Nuclear is a ‘convenient villain’

Hoff and Zeitz founded Mothers for Nuclear in 2016 to share what they had learned about nuclear energy.

“We’re not utility executives. We’re not guys in suits. We’re not mad scientists,” Hoff told CNBC. They’re mothers. They understand the doubt and the fear that nuclear power arouse, and then educate people about the science of nuclear energy in compassionate language.

The Mothers for Nuclear group has a couple thousand followers on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook. The group has evolved since its founding.

“When we first started Mothers for Nuclear, I think I was picturing our job as mostly being outreach to the public, but we have also grown into a role of being advisors to our own industry, and we spend a lot of time sharing about how we should all be communicating differently,” she told CNBC.

Not only does the nuclear industry do a poor job of advertising the benefits of nuclear energy, but it has, in many ways, hurt its own image by focusing on the safety precautions. Those extra layers of backup add cost, are often cases of operational redundancy, and send a subtle message that nuclear power must be terrifying and dangerous.

“It’s completely shot us in the foot,” Hoff said.

Given that Diablo Canyon is facing a very controversial closure, she knows some might think her nuclear advocacy group is cover for a public effort to protect her own job.

But she says it would be “a lot easier for me” to get a job working on a plant decommission or at another nuclear power plant elsewhere.

Instead, she says, she believes she has a calling to tell the story of nuclear power as a solution to climate change.

“The more I learn about nuclear and our energy options, the more worried I get and the more passionate I get, and the more I feel like it’s my duty to to speak out and help change people’s minds and help us realize that keeping existing plants open can help us address climate change — can help us reach our energy goals,” Hoff told CNBC.

Despite all the hurdles, Hoff is optimistic about some of the new advanced nuclear reactor technology being developed. And she says the energy sector really needs to get “a new bad guy.”

Notably, Hoff does not want to target fossil fuels as that bad guy.

“I also don’t want fossil fuels to be the enemy, because I think energy is so important for people to have a good quality of life and we need more energy,” Hoff said. “I don’t know, maybe the enemy is extremism — like people that aren’t willing to talk about the options and what’s the best combination of all the stuff that we have to do to make people’s lives better while also protecting the planet.”

— CNBC’s Magdalena Petrova contributed to this report.